Technology

From Food, Clothing, and Shelter to Internet: How Kerala Leads While Manorama Spreads Misinformation

Anusha Paul

Published on Jul 29, 2025, 07:26 PM | 6 min read

On July 28, 2025, Malayala Manorama—Kerala’s widely circulated daily—ran a sensational front-page story declaring the supposed failure of Kerala Fibre Optic Network (K-FON), the state's publicly owned digital infrastructure project. But stripped of its headlines and gossip, what the article actually delivered was something far more insidious: a textbook case of ideological sabotage masquerading as journalism.

Manorama’s report, curiously bereft of official data, field verification, or even a single quote from K-FON officials, was not merely sloppy, it was calculated. K-FON authorities have also made it clear that if false reports are not corrected, they will be compelled to take legal action. However, by presenting isolated user grievances as proof of systemic collapse, the publication chose to echo the anxieties of India’s corporate telecom elite rather than reflect the realities experienced by tens of thousands of Keralites for whom K-FON has been a digital lifeline. This wasn’t journalism; it was stenography for capital.

To understand why K-FON has become a target, one must look beyond the static of headlines and into the tectonic shifts occurring in India’s digital landscape. K-FON is not just an Internet Service Provider. It is an ideological statement, a material intervention, and a radical policy experiment. Launched in early 2021 and inaugurated in June 2023, it is India’s first state-owned Internet Service Provider (ISP), aimed at breaking the monopoly of private telecom giants and ensuring that access to the internet is treated not as a commodity, but as a fundamental right.

Kerala remains the only Indian state to formally declare internet access a fundamental right, embedding it within its framework of constitutional-style social provisioning. It is precisely this political audacity—this refusal to accept the digital enclosure of public life by capital—that has provoked the wrath of media houses and corporate lobbies alike.

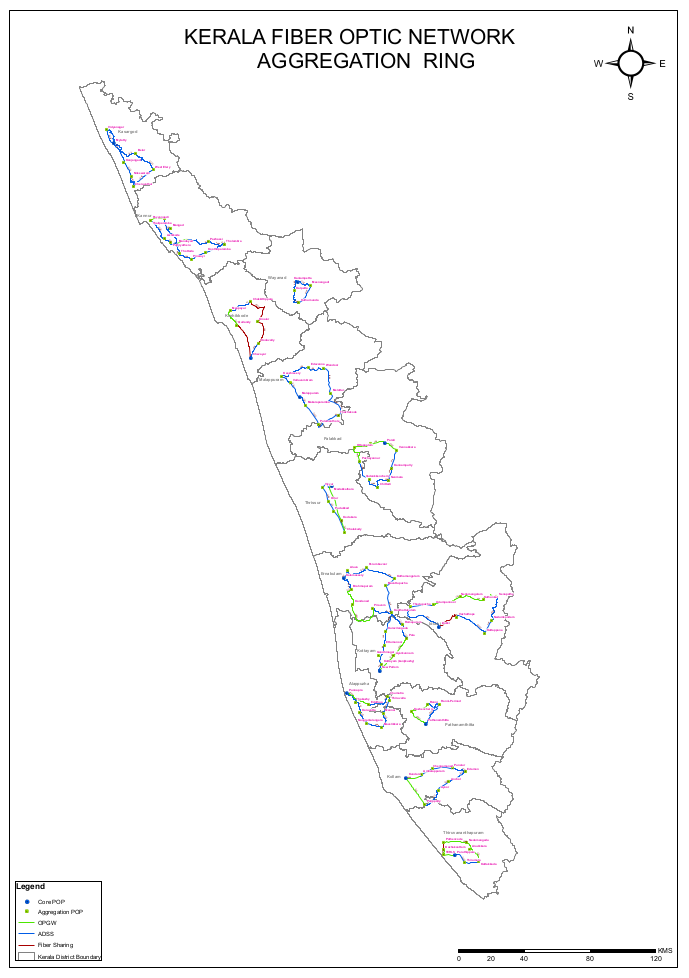

The numbers, as always, speak a language that profiteers cannot: as of July 2025, K-FON has connected over 1.12 lakh users across Kerala. This includes 71,925 individual homes, 14,194 economically backward families, 23,163 government offices, and 3,009 enterprises. These are not statistics—they are acts of defiance against a telecom industry that has, for decades, determined who gets to participate in the digital world and who does not.

K-FON has done what the market never cared to do. It has laid fibre across tribal hamlets in Attappady, the mountain tracts of Idukki and Pathanamthitta, and even remote island communities like Valanthakkad in Ernakulam—regions where no profit-seeking enterprise dared to go. In doing so, it has rewired Kerala’s geography of access, not for venture capitalists, but for schoolchildren, job-seekers, and village health workers. It has made the internet a public good, not a gated luxury.

Far from the fictional failure Manorama imagines, K-FON is today the primary digital backbone of the Kerala government. Every department in the state Secretariat uses K-FON. The Legislative Assembly switched to K-FON over a year ago. So did the National Health Mission, Technopark, KSRTC, KIIFB, Kerala Startup Mission, and more. These are not marginal users. These are mission-critical institutions where system failure is not an option. That they trust K-FON is the clearest evidence of its functionality and reliability. (Wikipedia)

Yet the attack persists. Why? Because K-FON’s very existence challenges the extractive logic of private telecom. It refuses to let a child’s future hinge on their family’s data plan. It denies capital its divine right to gate-keep communication, education, and public discourse. In a digital age, K-FON asserts that connectivity—like water, education, and health—is a right, not a revenue stream. This, to the ruling class, is intolerable.

We must also view this in the context of a larger global realignment in digital infrastructure. The rise of foreign-controlled satellite internet giants like Star-link (SpaceX) and Project Kuiper (Amazon) is not just about technological advancement. It is about the centralisation of planetary communications in the hands of a few corporations tethered to foreign intelligence and military establishments.

Star-link, though marketed as just a satellite internet provider, operates under U.S. laws like FISA Section 702—a legal provision that allows American intelligence agencies to collect data on foreigners outside the U.S. without a warrant. This means any information passing through Starlink’s systems, even if it belongs to citizens of other countries, can be legally accessed by U.S. surveillance agencies. In this sense, Starlink is not merely an internet provider; it is part of a global surveillance and control network. It operates with no commitment to the national sovereignty of the countries it serves, and it is not accountable to their democratic institutions or privacy protections.

Reports have already revealed that unlicensed Star-link terminals were used by militant groups in conflict-hit Manipur to bypass government blackouts. In India, Star link's illegal entry attempt in 2021 led to a regulatory halt. India's telecom oligarchs—Reliance Jio and Airtel—initially resisted Star-link to protect their turf. But market logic has no loyalties. Today, both are in active partnership with global satellite firms, effectively facilitating the outsourcing of national infrastructure to transnational digital capital.

K-FON, in contrast, represents the only serious counter-model. A model rooted in public ownership, local governance, and social accountability. A model that rejects profit as the primary metric and instead centers human need. In a world rushing toward data extractivism and digital feudalism, K-FON is a breath of democratic air—a form of digital socialism in practice.

But what distinguishes K-FON is its transparency and commitment to self-correction. It has a 24x7 toll-free helpline, dedicated field teams, and rapid escalation mechanisms. Unlike private ISPs, whose helplines are often black holes, K-FON is built on public accountability. When government departments request upgrades or support, they receive them—without bureaucratic apathy or market delay.

Yet none of this found a place in Manorama’s narrative. The publication did not ask for official data. It did not speak to K-FON’s leadership. It made no attempt to understand the historical, infrastructural, or geopolitical dimensions of the project. Instead, it gave its readers a story tailored for telecom boardrooms, not people’s movements.

Malayala Manorama’s recent distortion of the K-FON project is not an isolated incident but part of a long-standing pattern of manipulated reporting, especially on critical socio-political and economical issues. Over the years, the paper has repeatedly presented selective narratives that favour entrenched interests, often sidelining the realities faced by ordinary people and communities.

When corporate media vilifies state-led infrastructure projects like K-FON, it performs a discursive function: to legitimise the public sector, reinforce the hegemony of private capital, and ensure that alternatives to market rule are ridiculed, not studied.

K-FON is not a commercial venture. It is a political intervention, an assertion that even in the digital realm, the people—not the profiteers—must decide what is essential, what is just, and what is possible.

The future of India's digital architecture is at a crossroads. Will we hand over our networks, our data, and our sovereignty to billionaires in Silicon Valley and Mumbai? Or will we build a public digital commons, rooted in equity, democracy, and collective ownership?

0 comments