Unearthing Keezhadi: Who Wants the Past Buried and Why It Disturbs the Vedic Narrative

Anjali Ganga

Published on Sep 28, 2025, 01:19 PM | 4 min read

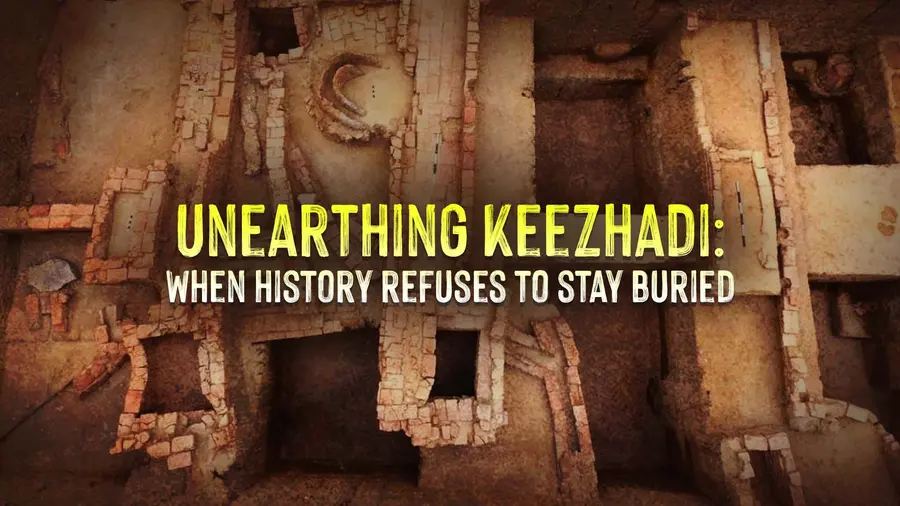

Keezhadi/Madurai: In India, the past is rarely just history, it often reflects the struggles of the present. In the quiet village of Keezhadi, along the banks of the Vaigai River near Madurai, a discovery in 2015 quietly began to challenge long-held ideas about the origins of Indian civilisation.

What started as a routine excavation by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) soon revealed traces of a sophisticated urban settlement, dating back to at least the 6th century BCE. Beneath layers of soil, Tamil Nadu’s forgotten past was emerging, raising questions not only about history but also about who decides which stories are remembered, and which are left buried.

Artifacts that Rewrite History

Beneath the soil lay a sophisticated urban settlement dating back to at least the 6th century BCE, showing that Tamil society was literate, urbanised, and culturally advanced centuries before northern cities in the Gangetic plains. For many in Centre, these findings were inconvenient, they challenged the North- centric, Sanskritised version of Indian history long promoted in textbooks and public discourse.

Under the leadership of K Amarnath Ramakrishna, the excavation unearthed over 5,500 artifacts, including Tamil- Brahmi inscribed potsherds, gold and ivory ornaments, terracotta dice, spindle whorls, beads, and tools related to pottery and textile production.

Brick-lined structures, water channels, and drainage systems pointed to careful urban planning. Radiocarbon dating confirmed habitation as early as 580 BCE, and graffiti symbols resembling the Indus Valley Civilisation suggested continuity between northern and southern cultural traditions. Evidence of long-distance trade, including Roman coins and foreign beads, revealed that Keezhadi was part of far-reaching commercial networks.

The site’s discoveries also reinforced links between material culture and Sangam literature, proving that Tamil society was literate and urbanised long before Sanskrit or northern influences became dominant. Thousands of artifacts, from terracotta figurines and iron tools to spindle whorls and dice, paint a vivid picture of a thriving craft, trade, and civic culture. Keezhadi demonstrates that urbanisation and literacy developed independently in South India, directly challenging Aryan-centric historical paradigms.

Central Government and the Erasure of Regional History

Yet, despite these groundbreaking discoveries, the ASI halted excavations after Phase III in 2017, citing a lack of “significant findings.” Ramakrishna was transferred to a largely inactive post in Uttar Pradesh, a move widely seen as punitive and politically motivated.

In 2023, he submitted a detailed 982-page report documenting the findings, only for the ASI to return it in 2025, demanding revisions that would downplay the dating and historical significance. Ramakrishna refused, citing scientific integrity.

K Amarnath Ramakrishna

K Amarnath Ramakrishna

Critics saw these actions as part of a broader attempt by the central government to erase or dilute regional histories from textbooks and public memory, suppressing evidence that contradicts the North-centric narrative of Indian civilisation.

CPI M MP Su Venkatesan called it “relentless hunting” to control India’s past, while historian R Balakrishnan noted, “Keezhadi is the first site that transformed the understanding of archaeology in Tamil Nadu.”

Tamil Nadu’s Independent Excavation: Pride and Persistence

In defiance of these political pressures, the Tamil Nadu state government resumed excavation independently in 2018, following a Madras High Court order. State- led efforts continued to uncover evidence of urban planning, literacy, industrial activity, and long-distance trade, reaffirming Keezhadi as a sophisticated settlement of the Sangam period. For Tamil Nadu, Keezhadi has become a symbol of regional pride and cultural resilience, a declaration that the state’s heritage cannot be rewritten or suppressed by political interests from the centre.

Keezhadi’s significance is immense. Its discoveries challenge Aryan- centric historical paradigms, provide material evidence to support Sangam literature, and demonstrate the advanced urban and secular culture of early Tamil society. The site offers thousands of artifacts, including terracotta figurines, iron tools, semi-precious beads, dice, and industrial implements, highlighting a thriving craft and trade culture. Graffiti resembling Indus Valley symbols reinforces cultural continuity between north and south. Roman coins and foreign beads reveal that the settlement was part of extensive trade networks.

The Politicisation of history

The Keezhadi episode exposes the dangers of politicising archaeology. The halting of excavations, the transfer of key personnel, and attempts to revise official reports illustrate how history can be manipulated to reinforce ideological narratives. By trying to suppress evidence of a literate, urban, and independent Tamil civilisation, the central government has attempted to control whose stories are told and whose achievements are recognised.

Today, Keezhadi stands as a testament to the resilience of regional identities, the pursuit of scientific truth, and the struggle to preserve history from political erasure. Its bricks, inscriptions, and artifacts are not merely remnants of the past, they are evidence that history is diverse, contested, and invaluable. Keezhadi reminds India that uncovering the past is not only an academic pursuit but a fight for memory, identity, and justice against those who would bury inconvenient truths.

0 comments