Emergency Crushed Workers’ Rights Alongside Civil Liberties, Writes Brinda Karat

Web desk

Published on Jun 25, 2025, 04:02 PM | 4 min read

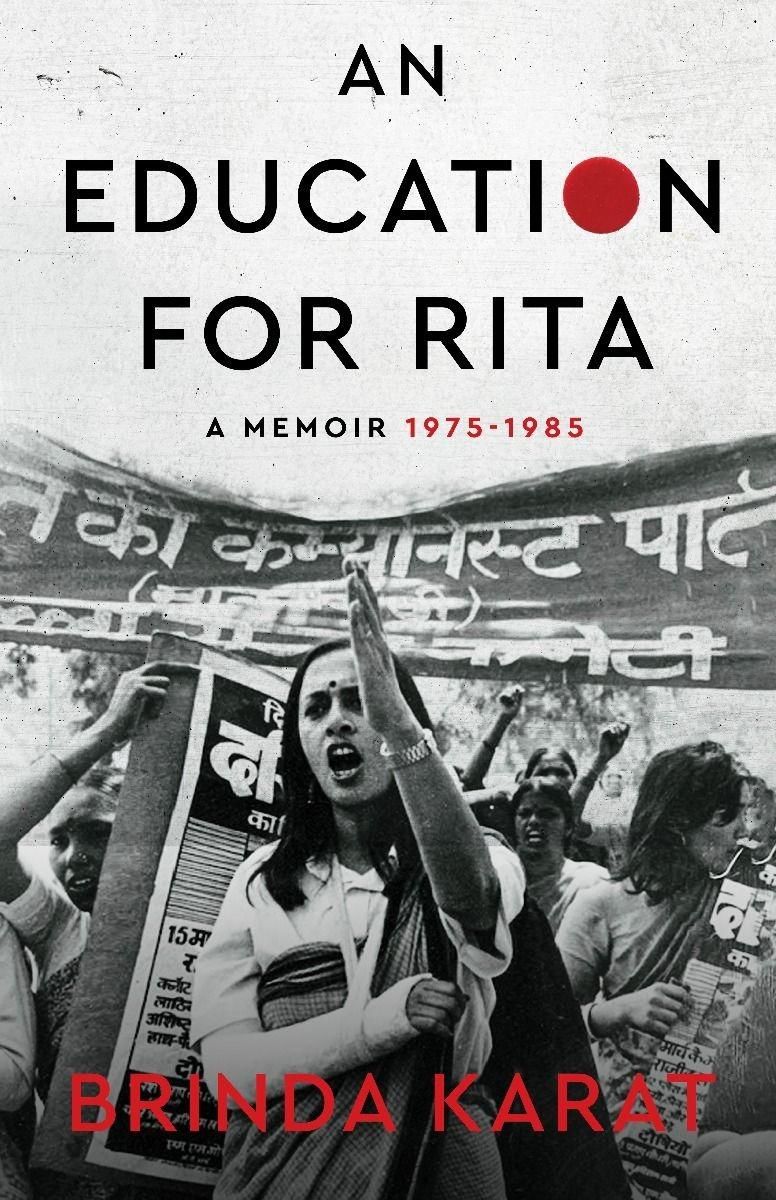

On the anniversary of the Emergency, veteran CPI M leader Brinda Karat has drawn renewed attention to a lesser-acknowledged consequence of the 21-month authoritarian period, the systematic dismantling of workers’ rights.

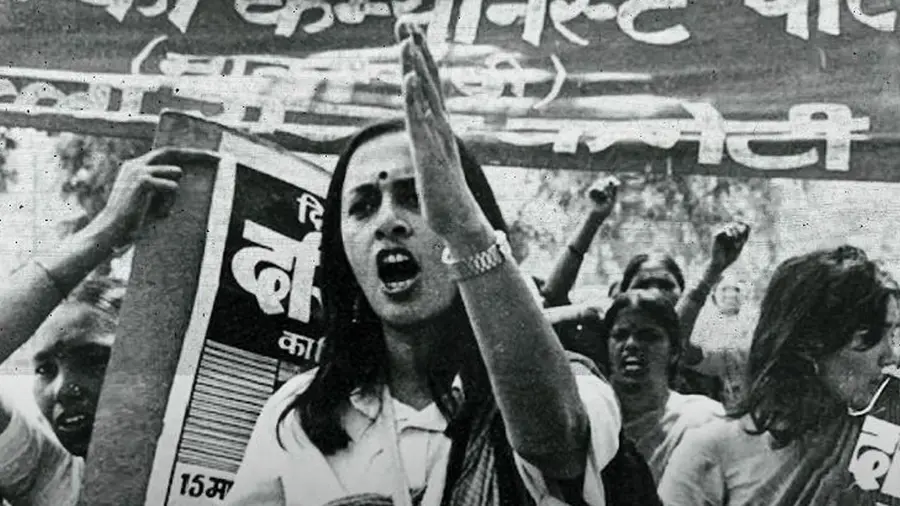

In her new book An Education for Rita, Brinda revisits her time as a young activist in the mid-1970s and highlights how the Emergency not only silenced political opposition and muzzled the press but also left the working class stripped of their hard-won rights to unionise, strike, and protest.

Recalling events from April 1976, Brinda writes about the plight of workers at the Birla Cotton Textile Mill in Delhi, where the management forced each worker to handle four looms instead of two and imposed longer working hours. As the clampdown on dissent intensified, workers found themselves with no legal avenue to resist. “The Emergency eliminated the basic right to unionise, to protest, to strike,” Brinda notes. “It disarmed the working classes of their hard-won rights.”

At the time, Brinda had been assigned by her party to work closely with labourers in the Birla mills and surrounding worker colonies in Kamla Nagar. She recounts how the strike that eventually erupted on the night of April 18, 1976, had to be organised entirely in secret. Meetings were held quietly, and leaflets were covertly distributed in places where workers would find them without drawing attention. “We used to leave the leaflets where we knew workers would walk past and they would pick them up and put them in their pockets discreetly,” she writes. “Before the strike, we smuggled leaflets inside the factory and placed them on each machine.”

According to Brinda, this underground mobilisation was a direct response to the hostile environment created by the Emergency, which empowered industrial managements to suppress dissent and extract more labour without accountability. “The Emergency allowed owners to do what they could not have even dreamed of earlier. It followed a wave of major worker strikes across India, including the 1974 railway strike, that had unnerved both the government and industry,” she said.

Brinda also documents the impact of the Emergency on Delhi’s urban poor, particularly the widespread demolitions carried out in the name of "beautification." Workers living in slums were forcibly evicted and relocated to the outskirts of the city, to areas like Nand Nagri and Jahangirpuri, then barren lands with no access to roads, water, or electricity. “Today, the scale of that brutal relocation has been forgotten,” she writes, pointing out that those displaced had to construct their own makeshift shelters.

Nearly five decades later, Brinda found herself once again in Jahangirpuri, this time standing in front of a bulldozer in 2022, protesting the demolition of homes, this time without any attempt at relocation. “The difference between then and now is that people were at least relocated. Today, demolitions are happening without any alternate provisions,” she said.

Brinda draws a link between the Emergency- era policies and current labour reforms under the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, describing the new labour codes as an “incremental attack” on the rights of workers, masked as reform. She accuses the government of using its parliamentary majority to marginalise the voices of the poor and working class. “Today’s assault on democratic rights is more dangerous,” she argues, “because it happens under the guise of democracy. The rights of Parliament and the Opposition are being systematically diluted, and the very function of Parliament is being redefined.”

The Emergency, declared by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi on June 25, 1975, following a Supreme Court stay on a verdict that voided her election, lasted until March 21, 1977. During this period, civil liberties were suspended, opposition leaders jailed, and press freedom strangled.

Brinda’s book serves as a powerful reminder that the Emergency’s authoritarianism extended far beyond high politics, it penetrated factories, working-class neighbourhoods, and the daily lives of labourers whose struggles remain on the margins of mainstream historical accounts.

0 comments