Health

Headlines and Half-Truths: How Malayala Manorama Distorts Kerala’s Public Health Story

Anusha Paul

Published on Jul 10, 2025, 08:53 PM | 13 min read

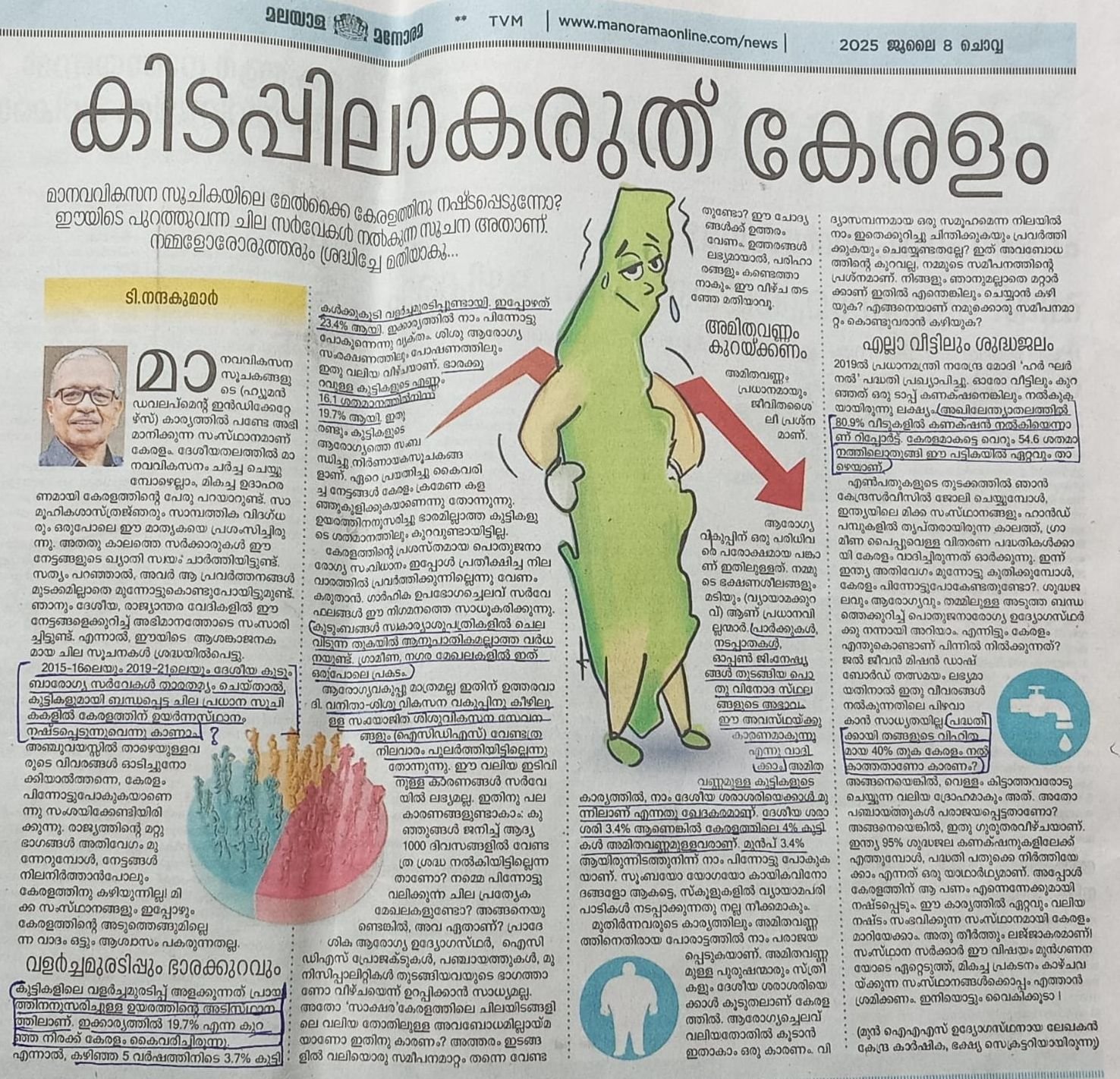

On July 8, 2025, the editorial page of Malayala Manorama—a media house owned by one of Kerala’s most powerful business conglomerates and a dominant force in the state’s mainstream newspaper—published an article titled "Kidappilakaruth Keralam" ("Do Not Let Kerala Be Bedridden"), authored by former IAS officer Dr. T. Nandakumar.

The report, largely filled with verbose commentary, nevertheless touches upon certain critical issues that can be interpreted as serious concerns regarding the functioning of Kerala's public health sector. While the author did not present a data-driven argument, he compared the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) of 2015–16 with that of 2019–21, focusing on childhood stunting rates to begin with. According to the reports, the stunting rate rose from 19.7% to 23.4% during this five-year period—an increase of 3.7%. Similarly, the percentage of underweight children increased from 16.1% to 19.7%.

Granted, this is data that is now four years old. Nevertheless, it was released by the Union Government. Although the reliability of NFHS data has been questioned over time, for the sake of argument, let us accept it at face value. Based on these figures, it is evident that over the past five years, Kerala has witnessed a rise in the number of children affected by stunting and under-nutrition.

It is also important to note that 2021—the final year covered by NFHS-5—was marked by the global aftershocks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Kerala, in particular, faced the highest and earliest recorded numbers of COVID-19 cases in the country at that time. The state was still navigating the long shadow of the pandemic, attempting to recover from both its health and socio-economic impacts. These circumstances inevitably influenced public health, including child nutrition, and must be taken into account while interpreting the data.

Interestingly, another study—this one conducted by Harvard University—noted that states generally regarded as better performers in health indicators, such as Kerala and Goa, are now showing an increase in childhood stunting. Himachal Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, and Haryana also appear to be following the same trend.

Yet, whenever such comparisons are made, right-wing media outlets—particularly Malayala Manorama, which often acts as a flag-bearer for those seeking to undermine the public health sector—quickly ask: “Why bring in other states?” The answer is simple. India is a union of states, and the federal system is what keeps this engine running. Before delving into the fractures in India’s federal structure, let’s return to the core issue: the stunting rate. It is, indeed, a health emergency—in Kerala as well as in other states.

The increase in stunting and underweight children in Kerala is not evenly distributed—it is disproportionately concentrated among the tribal population, a fact conveniently overlooked by both the author and Malayala Manorama. Studies show that stunting among tribal children stands at 33.2%, compared to 23.4% among non-tribal children. This disparity becomes even more alarming in Attappadi, one of Kerala’s most well-known tribal regions, which recorded 136 neonatal and infant deaths between 2012 and 2021.

Even after an investment of Rs. 131 crore in the region, children continue to die. That fact was acknowledged in a Malayala Manorama article at the time, underscoring just how grim the situation has become. These numbers are deeply distressing by any measure, especially when placed against Kerala’s overall infant mortality rate of just 6 per 1,000 live births—the lowest in the country.

In response to this worsening crisis, the CPI(M)-led Left Democratic Front government, which returned to power for a historic second consecutive term, appointed a six-member committee to assess the conditions in Attappadi. The committee, chaired by former University of Kerala Vice-Chancellor Dr. B. Ekbal, submitted its report to the CPI(M) State Committee. It called for a comprehensive health and nutrition survey in the region and proposed relocating the planned medical college in Palakkad—funded under Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe welfare schemes—to Attappadi. The report further recommended reserving half the seats at the college for tribal students, ensuring that future medical and paramedical professionals would come from within the community itself.

In the wake of these urgent findings, the Kerala government introduced several targeted welfare programs aimed at addressing child malnutrition more effectively. One such initiative was the Poshaka Balyam Scheme, launched on August 2, 2022. This program specifically targets children aged 3 to 6 years attending Anganwadis, providing them with milk and eggs twice a week to improve their nutritional intake.

Kerala’s decentralized governance structure—particularly the role of Local Self Governments (LSGs)—has been central to the implementation of such health and nutrition interventions. These bodies not only support delivery mechanisms but also play a vital role in community mobilisation and outreach.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when Kerala was grappling with surges in cases—especially during May and August 2021—the Women and Child Development (WCD) Department undertook innovative steps to maintain food security and child nutrition. These included the distribution of grocery kits through the Public Distribution System, with support from LSGs and community-led initiatives.

The issue of stunting and underweight children cannot be reduced to nutritional deficiency alone—it is deeply rooted in a web of socio-political and economic factors. The long-term impacts of under-nutrition go far beyond the physical. In tribal regions, where cultural marginalisation and systemic neglect intersect, the consequences are even more pronounced—affecting not just individuals, but the future of entire communities.

Recognising the seriousness of this multifaceted crisis, the Kerala Government developed a more comprehensive response. The plan extended beyond providing immediate nutrition, aiming to tackle the structural causes of deprivation. It included distributing land to the landless, providing secure housing, offering skill development training, and ensuring consistent maternal nutrition starting from early pregnancy. The plan also emphasized the education of the girl child—a critical factor in breaking the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition. These measures, taken together, reflect an attempt to shift from reactive welfare to sustained social transformation.

Expenditures in 2022–23 (in Lakhs): Table 1

Project | Year | Allocation | Expenditure |

Residential Schools | 2022-23 | 5000 | 6320 |

Rehabilitation of landless tribal population | 2022-23 | 4900 | 6791.99 |

Sickle Cell Anemia | 2022-23 | 1650 | 1646.2 |

Food Security | 2022-23 | 2500 | 2198.12 |

Health Care | 2022-23 | 2600 | 2150.96 |

Janani Janmaraksha | 2022-23 | 1650 | 1646.2 |

The article then moves on to discuss the increasing obesity among children in the state, stating that 4% of children are affected by obesity. The Kerala Health Department has also integrated obesity reduction into the state's targets under the National Nutrition Mission (NNM). A historic regulatory step taken to control rising obesity was the implementation of a "Fat Tax" on certain food items. The Kudumbashree project, known as FNHW, also aims to ensure better access to nutrition, health, sanitation, and drinking water for women and children.

The Kerala government has initiated the establishment of open-air gyms to encourage physical fitness among the public. In the first phase of this initiative, seven outdoor fitness equipment facilities were arranged, with an allocation of Rs. 20 lakhs approved for each gym. These initial open gym locations include Malappuram Kottakkunnu Park, Kalpetta Jinachandran Stadium, Akkulam Tourist Village, Thiruvananthapuram Central Stadium, an area near Alappuzha Lighthouse, Kozhikode Beypore, and Muzhappilangad Beach in Kannur and so on.

Additionally, the Kerala Public Works Department (PWD) plans to construct parks and open gyms under city flyovers, utilising available space to create recreational areas that may also include badminton courts, chess blocks, cafes, and restrooms. The government has also decided to establish healthy walkways in all 140 Assembly constituencies to help prevent and control non-communicable diseases.

(Image Courtesy: Suresh Kumar C via The Hindu)

The Healthy Kids program seeks to improve children's physical and mental abilities by introducing them to sports, with a primary focus on developing aptitude that can be honed through systematic training. It includes digital content for health and physical education for primary school students and pedagogical training developed by the State Council of Educational Research and Training for upper primary students.

The Sports for Change program, benefiting over 1,700 children across seven Community Sports Hubs in Kerala, provides free professional football coaching, life skills training, and awareness campaigns to foster a healthier generation. The Kayika Kshamatha Mission (Physical Fitness Mission) aims to improve the physical fitness levels of students and the general public while raising awareness about physical health.

Additionally, Kerala has developed a Total Physical Fitness program for school-going children. As of July 2025, a Zumba dance program was launched in Kerala schools to ensure physical fitness among youth. The Arogyakiranam program, a state-run health entitlement scheme, addresses the healthcare needs of children aged 0 to 18 years in government hospitals across the state.

The narrative of the article then slowly shifts towards the Union Government’s “Har Ghar Jal” project, accusing the Kerala Government of not paying its 40% share. Over the past years, the people in non-BJP-ruled states like Kerala have been underfunded and denied their rightful federal entitlements, and the article subtly frames this as a failure of the state government.

(Image courtesy: PTI)

Kerala, a tropical state with the one of the highest rainfall in the country, has traditionally relied heavily on well water for domestic needs, with over 85% of households depending on open wells. The state is known for its abundant groundwater and surface water resources, including 44 rivers, thousands of streams, lakes, and lagoons.

Water management in Kerala has historically involved community-managed open wells and the efforts of the Ground Water Department, which conducts hydro-geological investigations, drilling, and water quality testing. In 2023, Kerala became the first state to adopt a water budget to manage its resources effectively, ensuring equitable distribution and eliminating summer shortages. The Mazhapolima participatory well recharge program also supports rainwater harvesting to recharge open wells.

And then the real agenda behind the commissioned editorial begins to surface. Without citing any study, the author claimed that both rural and urban Kerala are suffering due to rising dependence on private hospitals. The argument is framed around disproportionate out-of-pocket expenses in the private sector, painting a picture of a public health system on the brink of collapse.

But here lies the irony: just six months ago, the Kerala Private Hospital Association (KPHA) publicly claimed that private hospitals were dying in the state. Now, the same media ecosystem that often echoes private sector interests seems to have rediscovered its concern for public health—conveniently framing it in ways that undermine the public health system and amplify the narrative of private sector indispensability.

It is also important to note that Karunya Health Insurance Scheme, a fully funded insurance program by the state government which covers Rs. 5 lakh per family per year for secondary and tertiary care hospitalisation covering the economically weaker sections, botton 40% of Kerala, and launched in 2019, which covers 42.5 Lakh people and about 400 private hospitals being participants in the scheme. In the year 2022-23, the total expenditure under this program was 1629.72 crores.

It is also worth noting that no one from the Kerala Health Ministry, LDF, or CPI(M) blamed Dr. Haris Chirakkal, Head of the Urology Department at Thiruvananthapuram Medical College, who raised concerns over equipment shortages or tried to cover-up. As soon as his social media post gained attention, the Health Ministry promptly set up a four-member committee to investigate the issue.

What happened in Kottayam was unfortunate. The building had been abandoned for years, with notices issued since 2012 advising against its use. While the incident was indeed tragic, it is being weaponized to portray public hospitals as inefficient—a calculated move to discredit a system painstakingly built by successive women health ministers of the LDF.

Kerala’s approach to Universal Health Coverage (UHC) emphasises equitable access through a robust public health system. The state has heavily invested in government-run primary health centres and hospitals, which are predominantly used by lower-income groups. Data shows that public healthcare utilization is highest among the poorest households, indicating that public services serve as a critical safety net, reducing financial barriers to healthcare.

During the tenure of the United Democratic Front (UDF) government in Kerala (2011–2016), Universal Health Coverage (UHC) was weakened by chronic under-investment in public health infrastructure. Several Primary Health Centres (PHCs) lacked basic diagnostic facilities and staff, and the Karunya Benevolent Fund—meant to provide free treatment to the poor—faced severe delays in fund disbursal, with hospitals reporting unpaid dues of over Rs. 300 crore by 2016. Simultaneously, the UDF promoted public-private partnerships (PPPs) and insurance-based models, which shifted focus away from strengthening public delivery and widened access gaps for economically weaker sections.

In Kerala, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led National Democratic Alliance’s (NDA) approach to health policy has increasingly undermined the state’s efforts toward Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and eroded its federal rights. Centrally imposed schemes like Ayushman Bharat were rolled out without accommodating Kerala’s well-established Karunya Health Insurance Scheme, disrupting an already functioning state model. Repeated delays in fund disbursal for key schemes like the National Health Mission, Women and Child Development programs, and even COVID-19 reimbursements have hampered timely service delivery. Kerala has also faced discriminatory financial treatment, such as unpaid GST compensation and delays in releasing disaster relief and welfare funds.

Meanwhile, the Adani Foundation—the CSR arm of the Adani Group—has collaborated with the Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research (DMIHER) to create a global Centre of Excellence (CoE) for affordable healthcare and education. The group plans to establish two 1,000-bed multi-super specialty health campuses in Ahmedabad and Mumbai. These centers, aligned with Adani’s broader infrastructure investments (including airport expansion), will also include medical colleges and AI-driven healthcare innovation labs. Strategic advice for clinical practices is being provided by the Mayo Clinic, and Gautam Adani’s family is set to invest over Rs. 6,000 crore in the project. This ambitious expansion into healthcare is part of a larger corporate vision—but also raises questions about the increasing overlap of corporate interests with the public’s health.

This erosion of federal autonomy in healthcare under the Modi regime is not happening in isolation—it is part of a broader shift toward privatised, insurance-driven healthcare that mirrors the U.S. model. In such a system, access is heavily dependent on private insurance, leading to rising out-of-pocket expenses and the marginalisation of the poor. In India, this trend has created fertile ground for global corporate interests.

In 2023 alone, private equity and venture capital investments in the Indian health and pharmaceutical sectors surpassed $5.5 billion. U.S.-based firms like Blackstone invested over $1 billion in acquiring Care Hospitals and expanding KIMSHEALTH, creating a 4,000-bed hospital network. Similarly, Swedish firm EQT and Singapore’s Temasek boosted investments in institutions like Manipal Hospitals and Indira IVF.

As the Union government prioritizes central schemes and insurance-led models over strengthening public systems, the space for profit-driven healthcare continues to expand. These developments risk transforming health from a public good into a commodified service, where corporate control over access, pricing, and infrastructure threatens the foundational principles of equitable care—especially in states like Kerala that have historically built strong public health models rooted in social justice and decentralisation.

Kerala’s public health system, despite facing challenges intensified by the pandemic and socio-economic disparities, remains a vital pillar of equitable healthcare. The rising concerns around malnutrition and infrastructure gaps demand urgent, sustained public investment and inclusive policies—not a retreat into privatisation that risks deepening inequality. As media narratives increasingly spotlight supposed failures, it is crucial to question whose interests are truly being served and to reaffirm the state’s commitment to universal, accessible health for all its citizens.

0 comments