Entertainment

Frames of Freedom: Art, Censorship, and the Politics of Expression

Noufal Mariam Blathoor

Published on Aug 09, 2025, 08:31 PM | 8 min read

Art is the solace and joy that a person discovers amidst various struggles of life. There is no other medium like art that can illuminate itself and enlighten others. Censorship or content regulation has always been a creation and requirement of the ruling powers. In modern times, censorship begins to operate as a subtle method of polishing and restraining the natural flow of art. The punishment here is not overt, but covert. In a modern nation, citizenship also implies the extent of freedom experienced by its people.

What is the relevance of the filters of morality, nationalism, and religious orthodoxy between the artist and the audience? Should the anxieties and fears of governments be a burden to the conscience of a democratic society?

Image Courtesy: Research GateLenin once said, “Of all the arts, the most important for us is the cinema.” This thought arose during the formative years of both cinema and communist ideology. There was a revolutionary foresight that politically recognized the power of cinema. Even amidst the chaos of the 1917 October Revolution, Lenin found time to watch films. His subtle opinions on the form and content of cinema are evident in his conversations with Trotsky, one of the founding leaders of the Red Army. These discussions also expressed a desire to give cinema an independent existence — free from both commerce and government control. Through public screenings such as the 1920 film Way to Freedom at the Kremlin Palace, Lenin demonstrated both his political practicality and his people-oriented approach.

Image Courtesy: Research GateLenin once said, “Of all the arts, the most important for us is the cinema.” This thought arose during the formative years of both cinema and communist ideology. There was a revolutionary foresight that politically recognized the power of cinema. Even amidst the chaos of the 1917 October Revolution, Lenin found time to watch films. His subtle opinions on the form and content of cinema are evident in his conversations with Trotsky, one of the founding leaders of the Red Army. These discussions also expressed a desire to give cinema an independent existence — free from both commerce and government control. Through public screenings such as the 1920 film Way to Freedom at the Kremlin Palace, Lenin demonstrated both his political practicality and his people-oriented approach.

The lineage of socially committed filmmakers is also a history of state bans, exiles, and trials — from Eisenstein to Jafar Panahi. Among all art forms, censorship is most visibly enforced in cinema. The expressive and offensive power of cinema prompts regimes to tighten laws. The way totalitarian regimes have used cinema as a weapon is best exemplified by Hitler. Under his supervision, hundreds of inhumane propaganda films like Victims of the Past (1937) suggested that the disabled, especially Jewish disabled individuals, should be sterilized as they had no contribution to economic growth. Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, also served as the minister for cinema. Director Leni Riefenstahl created numerous propaganda films for Hitler during this period.

In India, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), headquartered in Mumbai under the central government, is the body that issues certificates based on film content. It was formed under the Indian Cinematograph Act of 1952. With the 1983 amendment to the Act, the board was reframed from being a censoring body to a certifying one. However, in practice, its stance remains largely unchanged. Though officially it only has the power to assign certifications like U, U/A, or S, in recent times it has become a tool for enforcing the political interests of the ruling parties.

When a nation faces internal crises, the focus and spending are directed toward defence and communication ministries. Departments like health, human resources, and education face severe funding cuts. Art forms like cinema are placed under constant surveillance. The act of censorship becomes akin to a skunk that emits a stench to protect itself — a form of preventive aggression. Under the guise of preserving national integrity, even thoughts, speech, sight, reading, writing, and memory itself are distrusted by the state.

Courtesy: The Revolver ClubThe history of censorship in Indian cinema dates back to colonial times. In 1921, Bhakta Vidur was banned by the British government because the character Vidur dressed like Gandhi. Post-independence, the governments continued to show the same hostility toward art. During the Emergency period, Indira Gandhi’s Information and Broadcasting Minister V.C. Shukla played the role of a modern-day Goebbels. The media was categorized into 'friendly,' 'neutral,' and 'hostile.' Reports prepared by the Justice Shah Commission and the K.K.K. Das Committee mentioned in detail the challenges faced by Indian cinema during that time. All government film funds, previously provided through the Film Finance Corporation (FFC, the predecessor to NFDC), were suspended. Many valuable films in the 1970s were funded through FFC.

Courtesy: The Revolver ClubThe history of censorship in Indian cinema dates back to colonial times. In 1921, Bhakta Vidur was banned by the British government because the character Vidur dressed like Gandhi. Post-independence, the governments continued to show the same hostility toward art. During the Emergency period, Indira Gandhi’s Information and Broadcasting Minister V.C. Shukla played the role of a modern-day Goebbels. The media was categorized into 'friendly,' 'neutral,' and 'hostile.' Reports prepared by the Justice Shah Commission and the K.K.K. Das Committee mentioned in detail the challenges faced by Indian cinema during that time. All government film funds, previously provided through the Film Finance Corporation (FFC, the predecessor to NFDC), were suspended. Many valuable films in the 1970s were funded through FFC.

When singer Kishore Kumar refused to attend a meeting called by Shukla, he was banned from All India Radio. Artists like Vijay Anand and Amol Palekar were blacklisted. National award-winning actress Snehalata Reddy was imprisoned under political pretexts, and her deteriorating health was ignored until her death. In contrast, lavish funds were given for films glorifying Indira and Sanjay Gandhi. The documentary Indus Valley to Indira was purchased and screened at triple the production cost, as revealed by the Shah Commission.  Suchitra Sen and Sanjeev Kumar in AandhiGulzar’s Aandhi (1975) was banned during its theatrical run, giving retroactive weight to the Emergency. The film was accused of violating the electoral code. The political satire Kissa Kursi Ka, seen as a parody of the Janata car project, had its master prints seized and destroyed by CBFC officials. It was the first Indian political spoof, featuring Shabana Azmi and Raj Babbar. In 1978, a remake brought the film back, reminding audiences of the silenced times.

Suchitra Sen and Sanjeev Kumar in AandhiGulzar’s Aandhi (1975) was banned during its theatrical run, giving retroactive weight to the Emergency. The film was accused of violating the electoral code. The political satire Kissa Kursi Ka, seen as a parody of the Janata car project, had its master prints seized and destroyed by CBFC officials. It was the first Indian political spoof, featuring Shabana Azmi and Raj Babbar. In 1978, a remake brought the film back, reminding audiences of the silenced times.

Post-Emergency, youth-oriented protest themes flourished in cinema. The 1978 film Nasbandi directed by I.S. Johar focused on forced sterilisations, and one of its songs was sung by Kishore Kumar in protest. Even today, right-wing governments continue the media intimidation initiated during the Emergency. Deepa Mehta’s Midnight’s Children (2012), based on Salman Rushdie’s novel, was pressured for cuts due to references to Indira Gandhi. Films like Khwahishon Aisi (2005), Indu Sarkar (2017), and Hazaaron Baadshaho (2017) faced similar censorship. The most recent target is Kangana Ranaut’s Emergency (2025), which faced backlash from the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee for not omitting scenes of Indira Gandhi’s assassination and the Punjab riots. Death threats were issued to CBFC members.

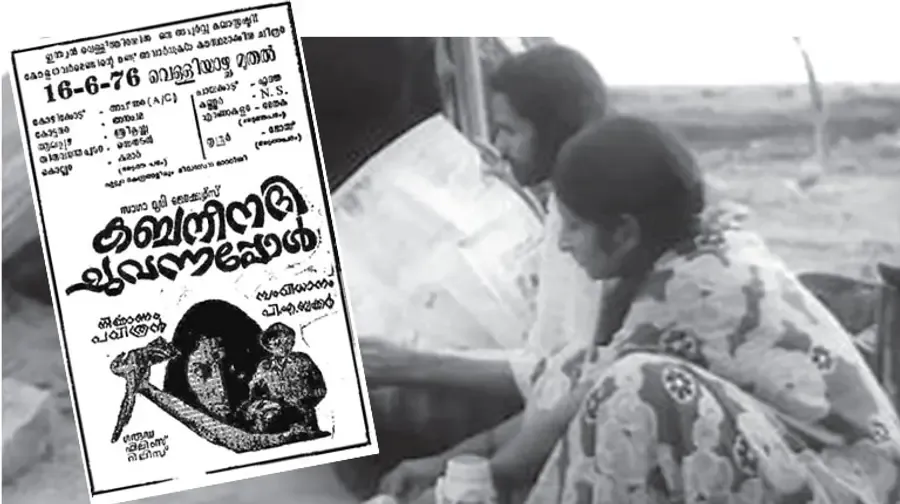

Malayalam cinema, too, was subjected to severe censorship during the Emergency. Kabani Nadi Chuvannappol (1976) survived due to the political awareness of its viewers. Despite resistance from the ruling Congress government in Kerala, the film received awards for Best Director and Best Film. Many other brave film projects emerged during this time. Others were butchered beyond recognition. Mrinal Sen’s Mrigayaa (1976), about the dreams of tribal emancipation, survived the censor’s scissors. The CBFC lacked the cinematic literacy to understand the film’s political Marxism and cinematic expression. At the end of Mrigayaa, a message reads: “Remember the martyrs who loved life and freedom in memory of them.” It was a call to resist the Emergency.

Malayalam cinema, too, was subjected to severe censorship during the Emergency. Kabani Nadi Chuvannappol (1976) survived due to the political awareness of its viewers. Despite resistance from the ruling Congress government in Kerala, the film received awards for Best Director and Best Film. Many other brave film projects emerged during this time. Others were butchered beyond recognition. Mrinal Sen’s Mrigayaa (1976), about the dreams of tribal emancipation, survived the censor’s scissors. The CBFC lacked the cinematic literacy to understand the film’s political Marxism and cinematic expression. At the end of Mrigayaa, a message reads: “Remember the martyrs who loved life and freedom in memory of them.” It was a call to resist the Emergency.

The government also used cinema to counteract cinema. On February 6, 1977, when Jayaprakash Narayan organized a massive anti-Emergency rally in Delhi, Doordarshan canceled the scheduled screening of Waqt and instead aired the popular film Bobby, hoping to distract the public. But this failed, and in the subsequent elections, Indira Gandhi lost.

In a time when the central government exhibits traits of religious nationalism and neo-fascism, the CBFC has become a tool to implement their agenda. An undeclared Emergency still looms over creative expression. Controls are normalised and made to seem natural. In Pathaan (2023), the CBFC demanded removal of references to RAW, the Prime Minister, and the Ashoka Chakra. Shunyato by Suvendu Ghosh was denied screening for its reference to demonetisation.

Image courtesy: Pravin Narayanan

Image courtesy: Pravin Narayanan

Unlike the past, current censorship adopts the garb of religious ideology. India's rich religious and cultural diversity is being undermined by this Hindutva mindset. The state interferes in film titles, funding, production, and awards. The demand to change the title of Janaki vs State of Kerala to Janaki V is a case in point. The argument is that ‘Janaki’ refers to a deity and must be kept separate from human figures. The Sangh Parivar attempts to divinize deities and monopolise their image, erasing the real-world lived connections. Censorship is their way of transforming emotional subjects into factual silences. Their attitude is: “We do not need questions from you; we will give you answers.”  Stills from the movie Udta PunjabInstead of cuts and mutes, mature content should be categorised by age and certified accordingly. The Bombay High Court’s observation on Udta Punjab must be recalled here — the public should be allowed to assess and interpret religious or political critiques on their own. Otherwise, censorship becomes a prejudiced simplification of public political and spiritual consciousness.

Stills from the movie Udta PunjabInstead of cuts and mutes, mature content should be categorised by age and certified accordingly. The Bombay High Court’s observation on Udta Punjab must be recalled here — the public should be allowed to assess and interpret religious or political critiques on their own. Otherwise, censorship becomes a prejudiced simplification of public political and spiritual consciousness.

Violent or sexually explicit films must be clearly rated under the ‘A’ category, and access should be restricted accordingly. Experts in women’s and child rights, as well as environmental issues, should be included in CBFC committees. The board must strive for moral and humane standards. It's a fact — as courts found — that pirated prints of the Malayalam film Premam leaked from the CBFC desk itself.

Art must remain as art, or it will devolve into a corpse of facts. Censorship’s mind must evolve to connect with cinema’s heart.

When writer U.R. Ananthamurthy was asked in his twilight years, “What kind of world do you dream of?” he replied, “A world where passports are not needed.” A country without borders is not just a child’s dream of flight — it is also a vision of a peaceful world built on mutual cooperation. Every artist longs for such a world — a world of art without censorship.

0 comments