‘No Sleep, Only Threats’: BLOs Reveal the Reality Behind India’s SIR Drive

“Suja’s BP increased, she had to be taken to the hospital in the evening. They are threatening each one of us,” an audio message shared in a WhatsApp group of Booth Level Officers (BLOs) in Kerala begins.

“They have been calling from 2 pm. They say all forms must be distributed by 5 pm. They are asking us to record even the undistributed forms as distributed. In the end, I stood on the side of a shop, scanned the forms and sent them,” another woman BLO says. Her voice is tired, but the frustration is unmistakable.

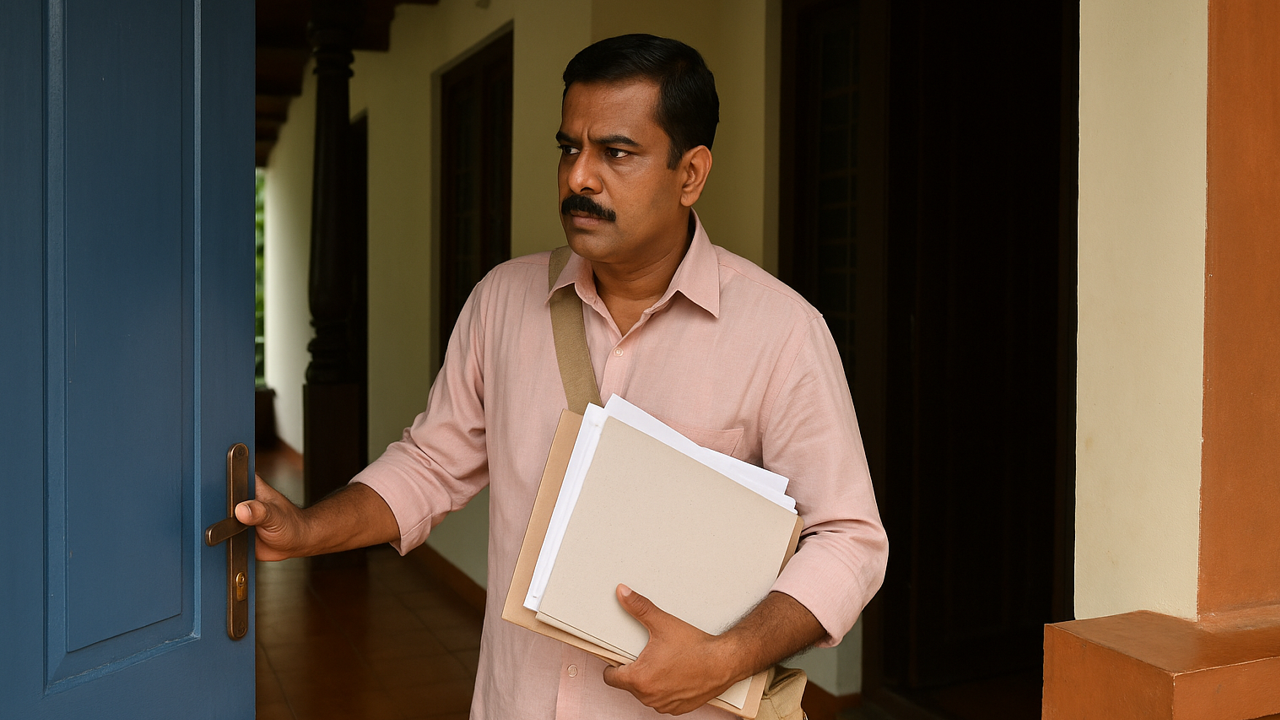

Discussions around the workload and pressure tied to the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) have sharpened in recent days, especially after the suicide of Kannur BLO Aneesh George. BLOs across the country describe the SIR as a schedule that barely allows them to breathe—long hours on the road, deadlines collapsing into each other, and supervisors tracking their movements through a day that rarely ends.

“Supervisors and village officers keep calling continuously. ‘Are you in the field? We are monitoring. You must be reachable whenever we call. Otherwise, there will be legal action including suspension’—this is the threat,” says R. Antony, a BLO in Thiruvananthapuram. His phone barely stays silent; each vibration signals another check, another reminder that someone is watching.

For some, the challenge begins even before fieldwork starts. “I was assigned BLO duty in a place away from my own village. I do not know the people or the voters there. I have to meet more than 1,500 voters in person and give them the forms. Finding them itself is a huge responsibility. How can all this work be completed within one month?” asks Prashanth, another BLO in the district.

The expectations placed on BLOs would challenge even a well-staffed team. They must visit over a thousand houses—often more than once—to distribute the forms. Women officers and those with health issues say they remain in the field from early morning till close to 10 pm. In many rural and interior regions, houses remain locked during the day when people leave for work, pushing BLOs to climb slopes and return to the same houses repeatedly.

“We are not getting enough sleep, and we face pressure to meet the target,” says Paulin George, a BLO from Kadavoor in Kollam. Fieldwork fills the day, and online meetings take over the night. Searching for voters who live outside the booth area stretches the workload even further. “We were sent out without giving any training,” she adds.

A deeper anxiety runs through many of these accounts—the fear of being pushed into practices that could later turn against them. BLOs say officers insist that all forms be shown as distributed, even when several remain undistributed. The fear is simple: what happens when someone later asks why they never received a form?

And the cycle does not stop with distribution. Once the forms are handed out, BLOs must collect them and immediately begin the next phase—scanning pages, photographing attachments, entering each detail into the Election Commission’s mobile app. They work without dedicated scanning devices, often using their own phones late into the night.

The app itself adds another layer of pressure. Undistributed forms appear in pink; the colour only shrinks once the BLO updates distribution. After collection, the pink turns blue. Only after scanning, verification, and data entry does the screen turn green. Officers must cross-check the 2002 SIR list with the 2025 list before entering anything. Many ask how such verification is possible when distribution itself remains unfinished.

Even with an additional BLO, the workload barely shifts. “We have informed higher officials about this, but no one takes it into account. They only say the work must be completed,” says Jijumon, a BLO in Thiruvananthapuram. Yesterday, a BLO in Kozhikode—Aslam, a senior clerk in the PWD—received a show-cause notice from Deputy Collector Gopika Udayan for allegedly failing in duties.

The strain is beginning to show on the ground. In Kasaragod, Sreeja, an Anganwadi teacher from Maikayam in Balal Panchayat, collapsed yesterday morning while doing SIR work. She was admitted to a private hospital in Konnekad.

Protests Across the Country

Kerala is not alone. Across India, BLOs are pushing back against the pace and weight of the SIR workload. In Rajasthan, anger intensified after Mukesh Jangid (43), a teacher on BLO duty, died by suicide by jumping in front of a train. His note said he could no longer bear the pressure and harassment from higher officials. Teacher organisations in the state have demanded that teachers be exempted from BLO duties during the half-yearly exams.

In North Kolkata, West Bengal, BLO Animesh Nandi collapsed during a meeting with his supervisor while on SIR duty. His family said he had been under severe work pressure. BLOs across several districts boycotted training programmes on Saturday.

In Tamil Nadu, the Revenue Employees’ Federation has announced a statewide boycott of SIR duties beginning Tuesday. Their demands include ending late-night review meetings and the practice of conducting three video conferences each day.

0 comments