Interview

From Kanpur to Kurla: In Conversation with Subhashini Ali on the Emergency Years

Anusha Paul

Published on May 23, 2025, 06:19 PM | 7 min read

You moved from Kanpur to Bombay in 1974 — just as India was approaching one of its darkest periods: the Emergency. From your arrival during the Railway Strike to the declaration of Emergency in 1975, how did this period shape your political and personal life — especially as a young woman, trade unionist, and someone newly navigating marriage?

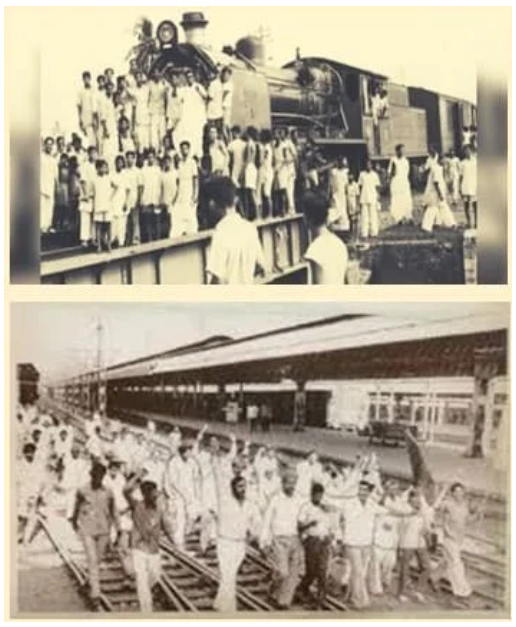

I arrived in Bombay in May 1974, right before the historic Railway Strike broke out. Personally, marriage was a jolt — I had grown up with complete freedom, and suddenly, I was expected to ask permission to adjust. But despite the domestic strain, I joined comrades from CPI(M) and CITU in solidarity actions. At Kurla, I participated in a railway track dharna, where we were literally dragged away by our hair by the police. The strike was crushed with repression. Indira Gandhi’s authoritarianism was clearly intensifying. It reminded many of what had already begun in West Bengal in 1972 — a laboratory of repression.

(Image: google)

In West Bengal, the CPI(M)-led Left Front had resisted the post-war pro-Congress wave. Indira Gandhi never forgave that. The 1972 assembly elections were rigged, and a Congress government was imposed. Over 2,000 CPI(M) supporters were killed. Women comrades were raped; thousands were displaced. I have vivid memories — our IEL Employees Union in Kanpur was part of the ICI Workers’ Federation. We had passed a resolution to go on strike in solidarity if any ICI unit saw repression. But in Rishra, our comrades said even a one-day strike could lead to police firing and deaths. Still, they staged huge demonstrations in solidarity, braving lathi charges. The media blackout made it worse — outside Bengal, people did not believe us.

(Image: Google)

Later, I travelled to Naihati, West Bengal, for a Jute Workers' Conference, representing JK Jute Mill Mazdoor Panchayat. Com. Jyoti Basu and Com. Kamal Sarkar addressed a massive rally. I nervously spoke too. Afterwards, I rode back to Calcutta with both leaders in total darkness, no security — just a Party volunteer. At the end, Basu said in his cool, sardonic way: “Well. Another lucky day.”

In Bombay, I entered a new phase of activism — especially through the women’s movement. Leaders like Ahilya Rangnekar and Vimal Randive had long organized working-class women. After the Party split, CPI(M) women formed the Shramik Mahila Sangh. I joined and became a lifelong women’s activist. Until then, I hadn’t experienced gender injustice personally, but in Bombay, it became vivid. I saw deprivation and discrimination — but also humor, generosity, and great affection in working-class lives.

Ahilyatai, tiny in frame but fierce in spirit, became a guide. As a municipal corporator, she’d take on cops and goondas alike. I watched her in meetings, in slums, in action. Her home was always open. In that alien city, she made me feel rooted.

( Ahilya Rangnekar and Vimal Randive. Image: Google)

And then came another life-changing moment — I became pregnant. My son was born in March 1975. Soon after, the Emergency was declared. Bombay, a hub of anti-government protests, was stunned. JP had addressed massive meetings here, even visited our Janasakti office where we greeted him with red flags and “Lal Salaam!” Political activity froze. Leaders were jailed. Ahilyatai was sent to Yerwada Jail with Mrinal Gore. A heavy silence fell across the city. The media was gagged. People were afraid. But a few brave voices — scattered but strong — kept hope alive.

My husband worked at Air India. One of Mrs. Gandhi’s first moves was removing Mr. Tata. from the Chairmanship, and in-spite all the chaos, it was wonderful. Some Air India officers spoke out — openly, courageously. I also took a job, which distanced me from politics. But in late 1976, Com. Meenakshi Kolhatkar invited me on a picnic to Elephanta with SMS women. That outing rekindled my activist spirit. I began attending secret meetings at comrades’ homes, then public hall meetings. The murmuring of dissent was growing louder.

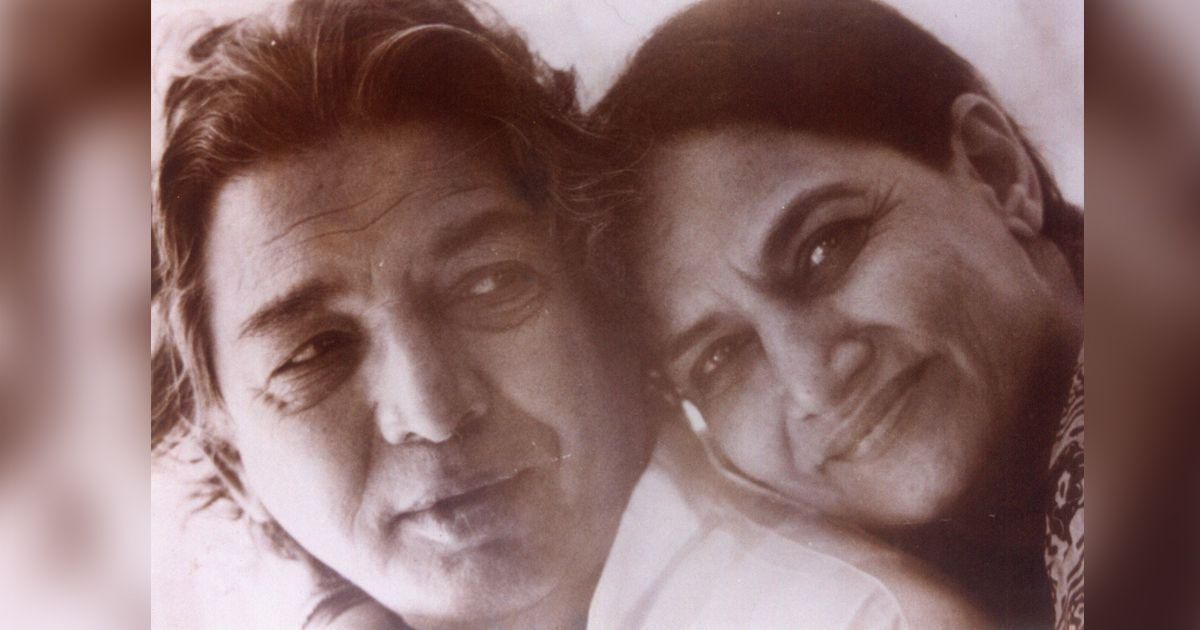

(Kaifi Azmi and Shaukat Kaifi, were a prominent couple in Indian theatre and film). Image: google)

I was also blessed with a support network — Kaifi Azmi and Shaukat Apa lived nearby. Their home was always open. Sardar Jafri, Sultana Apa, Rahi Masoom Raza — all intellectuals, mostly CPI-aligned — had differing views from mine, but our conversations were magical. Rahi Sab, in particular, stood out — I admired Aadha Gaon deeply.

I spent time with Suhasini Chattopadhyay, now Suhasini Jambekar, and her husband Com. Jambekar. They ran The New Work Center, teaching language and skills to women. Though CPI-aligned, they were incredibly warm. Despite political differences, we shared knowledge, stories, and solidarity. As months passed, news of torture, police brutality, forced vasectomies, rural displacements, and firing on protesters began spreading. The fear remained, but anger simmered beneath it.

Q2: What was the public response when elections were announced in 1977? How did the end of the Emergency reshape your activism and political engagement, especially during the Janata Party wave and the post-Emergency elections?

The announcement of elections in March 1977 was electric. We were in Maheshwar near Indore when it came. Within hours, that small town was celebrating. Across North India — Delhi, UP, Bihar, MP, Bombay — there was an eruption of joy. The repression of two years had kept people silent, but now the lid was blown off.

We took a train back to Bombay. At every station, people were gathered, cheering, waving, chanting slogans. Morarji Desai was on our train. I managed to sit near him and congratulated him on his release.

He beamed and said, “I have never been so popular in my life!”

With the Emergency lifted, censorship ended. The horror stories came flooding out — the torture, the sterilisations, the killings. There was euphoria, yes — but also rage. That energy forced the opposition to unite as the Janata Party. Our Party (CPI-M) did not join the merger but took part in the united campaign.

I quit my job to join the election campaign full-time.

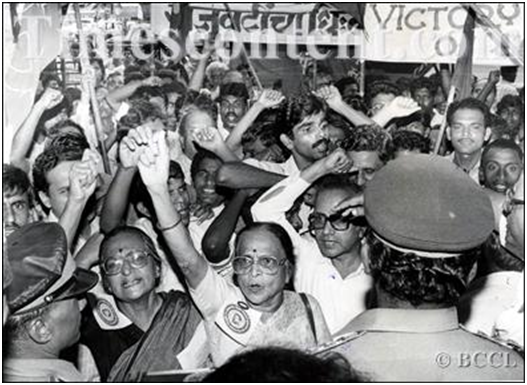

(Ahilya Rangnekarleads a demonstration outside British Deputy High Commission in Bombay in 1988. Image Courtesy: The Times Of India Group)

Ahilyatai was declared the united candidate of the Janata Party and CPI(M) from Bombay North Central. At a Party meeting, Com. BTR saw me and said I should campaign in Hindi — especially in Kurla, which had many workers from UP and Maharashtra. That pushed me back into full-fledged activism.

Campaigning was relentless — house-to-house visits, speeches late into the night. There was excitement, yes, but also exhaustion — and some domestic friction. Still, I felt alive in that campaign. When the results came, Congress was wiped out in North India and in all of Bombay. The Janata Party came to power. CPI(M) won a strong presence in Parliament, and Ahilyatai became an MP. Most importantly, the reign of terror in West Bengal finally ended.

That period — the Railway Strike, the Emergency, the election — reshaped my life forever. It sharpened my political convictions, drew me deeper into women’s rights, taught me resilience, and gave me lasting comradeship. Fifty years later, the memories remain vivid — of repression, resistance, and the hope that the people’s will can still prevail.

0 comments