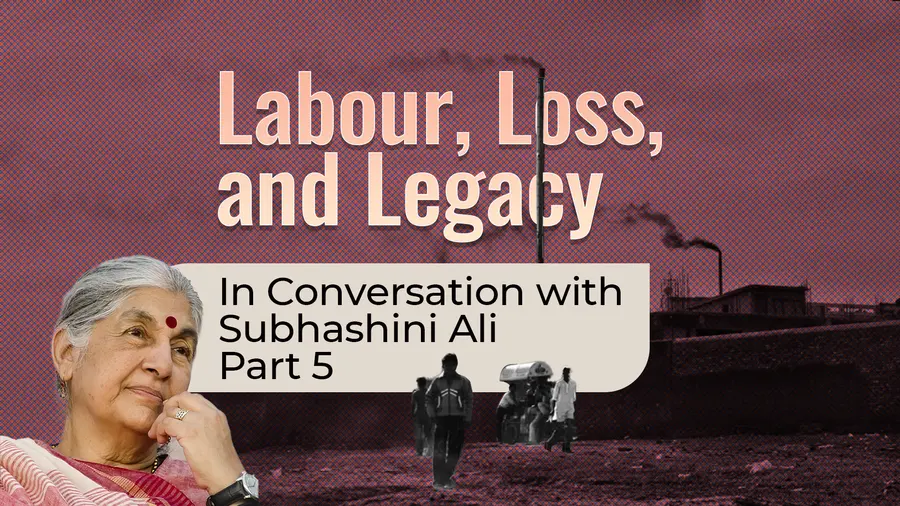

Interview

Labour, Loss and Legacy: In Conversation With Subhashini Ali

Anusha Paul

Published on May 15, 2025, 05:30 PM | 9 min read

The period leading up to the Emergency was a time of immense struggle for workers in Kanpur, marked by both economic hardships and intense union battles. Comrade Ram Asrey’s leadership played an important role in organizing workers through these challenges. His untimely death in 1973 was a significant blow to the movement. Can you describe what those turbulent times were like for the workers, how Comrade Ram Asrey’s loss affected the morale and direction of the union struggles?

The attack on the working class in Kanpur didn’t end with the victimization and lockout at JK Rayon. Another very strong CITU union was at IEL (ICI) Ltd., a new fertilizer factory owned by the British company ICI Ltd. This factory had been established in Kanpur in the mid-1960s. The workers at IEL were different from the textile workers, who were generally less educated and had strong ties to their villages. IEL workers, for the most part, were well-educated, often graduates with engineering degrees, and were quite young.

Comrade Ram Asrey understood that the trade union movement needed to include workers from newer industries like IEL and, to some extent, JK Rayon. Traditional industries like textiles were in crisis not only in Kanpur but across much of the country. Textile factories had started closing in Ahmedabad, Bombay, Calcutta, Madhya Pradesh, and other places. Many had been nationalized, including most of the mills in Kanpur, but the government showed little interest in investing money to modernize them, resulting in increasing losses. The privately owned mills were also struggling, and the threat of closure loomed large.

The textile industry’s crisis had various reasons, but the primary issue was that the mills were composite mills, combining spinning and weaving departments. After decades of struggle, the workers in these mills had secured regular wages, dearness allowances, and bonuses. Meanwhile, the spinning mills, where wages were much lower, had started proliferating, and the powerloom industry was rapidly expanding. These industries were largely unregulated, with no excise duty, poor labour law enforcement, and 12-hour working days. As a result, powerloom cloth was much cheaper than mill-made cloth.

Kanpur’s mills faced an additional handicap: they primarily produced sarees and cloth for poorer sections of society—chheent sarees and markeen cloth, which were priced cheaply, with no scope for raising prices. The mills also produced canvas in large quantities, a product that had seen huge demand during World War II. However, mill owners failed to reinvest the super-profits from that period into modernizing the mills. Additionally, intense rivalry between the large Marwari owners made the Kanpur mills even more prone to closure. Mills owned by British companies suffered further neglect, as management realized that it was time to close down operations.

By the mid-1960s, most mills were in crisis. The union government, at the time, followed a policy of nationalization for sick units, which resulted in the nationalization of British India Corporation, with its three textile mills and one tannery. The private mills that had closed remained closed.

When I came to Kanpur in 1969, Comrade Ram Asrey led a struggle for the nationalization of a private mill—New Victoria Mills—that had shut down. Most other trade union leaders opposed this struggle, calling it a hoax. Along with other young comrades who had joined the CPI(M), I became very active in the struggle and was tasked with meeting and organizing the wives of workers, persuading them to participate in the Court Arrest program.

This was an incredible opportunity for me—to get directly involved in a working-class struggle as soon as I had decided to join the Party. It was also a strange experience, as my father had been the General Manager of this particular mill for many years. Fortunately, he didn’t have a reputation as an anti-labour figure, so the workers’ families were kind and hospitable to me. The union leaders who opposed our struggle had a field day, making speeches about the manager’s daughter, whom they humorously claimed was probably a CIA agent since I had just returned from America! Despite this, the generous spirit of the workers and their families ensured I did not mind their attacks.

Our Court Arrest program was a success. The day we women courted arrest felt like a festival, with more than a hundred women agreeing to go to jail, accompanied by over a thousand men and women. Eventually, around fifteen of us were actually sent to prison. Since there were so many of us, it was not too difficult, and we were released after a few days. The impact of the struggle was so great that the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh—known for being anti-working-class—announced the nationalization of Victoria Mills.

While nationalization was a victory, it was not a permanent solution. The government showed no real interest in modernizing the industry. However, because of the strong movement supporting the textile workers in Kanpur, most of the nationalized mills remained open for over a decade.

It was prescient of Comrade Ram Asrey to turn his attention to newer industries. The union at IEL was formed with the help of a leader from the ICI Employees Federation, who came from Calcutta and met IEL workers to discuss forming a union. He connected them with Comrade Ram Asrey. I played a key role in forming the union, mainly because I had a little car! IEL was located far outside the city, and most workers lived far from the city center. I often drove Comrade Ram Asrey to meet the workers, and that’s how I became part of the union’s Executive Committee when it was registered.

After the JK Rayon struggle, it was IEL workers' turn to face victimization and fight back. The factory was about 15 kilometers from the District Court, and I remember several foot processions from the factory gates to the administration offices. I had mentioned earlier that the Labour Minister, Bajpai, was from Kanpur and lived near Comrade Ram Asrey’s neighborhood. Although he had been a trade unionist, he became extremely vindictive toward Comrade Ram Asrey and the CITU once he became Labour Minister.

During the IEL struggle, we took a procession past Bajpai’s house. He was furious and had both union leader Arvind and me arrested that evening. We were in jail for fifteen days—an odd experience. Fortunately, the management agreed to a settlement, and we were released.

Related News

This was when I became involved in organizing electricity workers in Kanpur. Shortly after our union was registered, the main AITUC state-wide union initiated a strike, but we had not been involved in its preparation. There was no strike in Kanpur, so Comrade Daulat and I couldn’t go to the gate because the police were after us. I remember wearing a burqa for three days to evade arrest. On the second day of the strike, I went to the Power House in my burqa, while Daulat hid in a tea shop. As the workers started coming out for their shifts, I jumped onto a stool, pulled back my naqab, and started speaking in support of the strike.

The workers had been waiting for this, and a complete strike followed. As it got dark, Daulat and I somehow managed to navigate through the bustee in front of the Power House and reach my home. The next day, an announcement was made that the strike had been withdrawn since the government had agreed to some of the workers’ demands. We had to go back to the Power House and make speeches urging the workers to return to work—which they did—and both of us were arrested. The CO who arrested us, Ahmad Hasan, was a decent man (he later became a Minister in the Mulayam Singh government). He took us to my house and handed us over to my father, advising him to keep us locked up for twenty-four hours.

In 1973, there were attacks on JK Jute Mill and IEL workers. Comrade Ram Asrey, who had been a heart patient, passed away on April 23. There were suspicions that he had been given adulterated glucose, leading to a coronary seizure. We were devastated. His body was placed in front of the Party office in Naveen Market, and hundreds of workers and supporters gathered in front of it all night.

That year, we fought to prevent a strike-breaking effort at JK Jute Mills, and I remember appealing to the blacklegs not to enter the mill. Even they were moved and went back. Comrade Ram Asrey’s funeral procession was historic—thousands of people took part, many of them weeping and chanting slogans. We felt orphaned, but we couldn’t even mourn properly because the struggles at JK Jute Mills and IEL continued.

Despite the struggles, the IEL union fought hard, and its members returned to work after some months. Unfortunately, the same could not be said for the Jute Mill.

The loss of Comrade Ram Asrey was a blow from which the working-class movement in Kanpur and the Left movement in Uttar Pradesh never really recovered. He was a visionary, intent on building a truly transformational trade union movement. Near the JK Rayon factory, the union built an office and a school that continues to operate today.

With limited resources, we started a fortnightly magazine, Mazdoor Rajniti, which was widely read among our union members. It was his dream to build a kisan movement alongside the workers' movement. Tragically, he passed away at just 47, and many of his dreams remained unfulfilled.

I continued my work in Kanpur for another year before moving to Bombay in April 1974. It was a difficult parting, and for months, I felt like a traitor… perhaps I was one.

When the Emergency was declared, I was in Bombay. A warrant for my arrest was issued, and it reached a shop in front of our office in Naveen Market. The shop’s owner, a politician who knew me well, told the cops that I had left but could leave the warrant with him if I returned. He later shared it with me.

0 comments