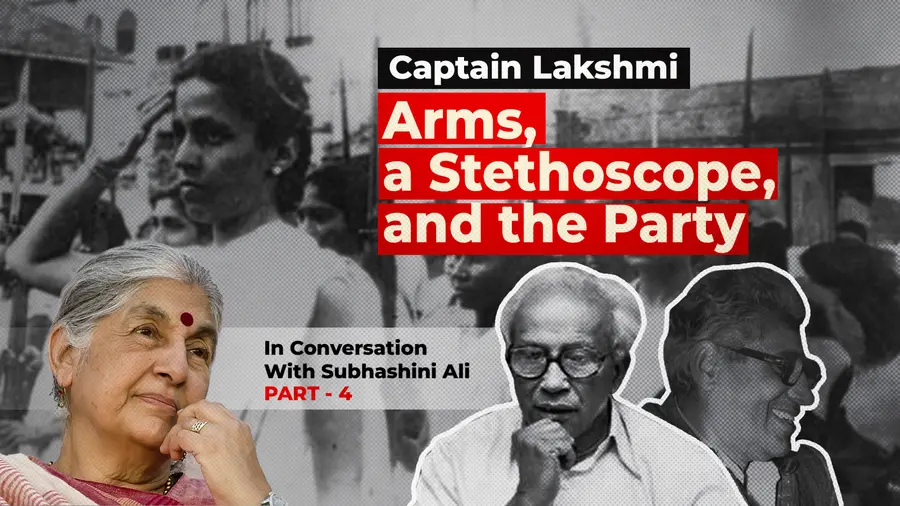

Interview

Captain Lakshmi: Arms, a Stethoscope, and the Party In Conversation with Subhashini Ali

Anusha Paul

Published on May 09, 2025, 01:05 PM | 9 min read

Captain Lakshmi was a patriot who took up both arms and a stethoscope in the fight for freedom—deeply inspired by Bhagat Singh and raised in a household shaped by your grandmother, Congress leader Ammu Swaminathan. Given that revolutionary fire in her from such a young age, what do you think held her back from formally joining the Communist Party until the age of 57? She was already deeply involved in helping the poor and working in areas of need—so what changed for her, and what did her political journey look like once she finally called the Party her home?

When she joined the Party in 1970, Lakshmi said that for her it was a homecoming. She was 57 at the time—probably one of the few instances in Communist history of someone joining a Communist Party at this age! The question that this raises is: if she felt that joining the CPI(M) was like a homecoming, then why did she take so long? She could have joined the united CPI decades before this.

To get answers to these questions one has to go back in time to her growing up. Lakshmi grew up in a household which, from the time she was very young, was filled with the hubbub of the national movement. In 1920, when she was barely six, she was organising children in the locality to collect foreign clothes from neighbours and then dancing around bonfires of these clothes and their own, precious foreign toys. She and her younger sister, Mrinalini, were taken out of the English-medium school where they were studying and put into a Tamil-medium school where they wore uniforms of the traditional pavade (long skirt worn with a tight blouse).

Lakshmi’s mother, Ammu Swaminadhan, was a prominent Congresswoman who led protest marches, organised boycotts of liquor shops and was also articulate in her support for campaigns for women’s rights. When Gandhiji gave a call to students to quit their schools, Lakshmi did not agree with this. She was also getting disillusioned with his tactics of ahimsa and satyagraha. She made two important decisions: the first was to collect money for Bhagat Singh’s defence and later to participate in the huge procession that organised a successful bandh in Madras when he was hanged; the second was to prepare to be a doctor. She was certain that free India would need thousands of dedicated and committed doctors and decided to be one of them. Her medical studies kept her busy for most of her years as a young adult and, while she hoped for a militant struggle for independence to emerge, she herself did not come in contact with Communists at that time.

It was in her last years of medical college that she met her first Communist—Suhasini Chattopadhyay, sister of Sarojini Naidu and the first woman to join the CPI. The Party was banned at the time and Suhasini took shelter in Lakshmi’s home where the two of them shared a room. The local police suspected that she was there but were never able to catch her. My mother recalled years later that Suhasini, who had lived in Europe for several years, enthralled her night after night with stories of the Russian Revolution, the tortures suffered by German Communists at the hands of the Nazis, and the epoch-making struggles of the Chinese Communists who were combating the cruelty of Japanese occupation and fighting for the emancipation of the peasants and workers in their country.

Suhasini had a wonderful, deep voice and she taught my mother the Internationale, which she sang with gusto at the Party Congresses she attended much later in life. Lakshmi continued to read and learn about Communism but her studies kept her busy and, soon after she got her degree, she left for Singapore.

The CPI was very harsh in its criticism of Subhas Bose and this naturally infuriated Lakshmi and my father. So, when she returned to India in 1946 and came to live in Kanpur, there was no possibility of her trying to join.

After I returned from America determined to join the Communist Party, neither of my parents tried to dissuade me. Their extremely democratic attitude toward both their daughters—allowing us to make decisions on our own—is something that I cannot appreciate enough.

Later, a meeting with Com. EMS while he stayed with us and the discussions they had with him did much to assuage their feelings. Once I joined the CPI(M), Lakshmi was very influenced by Com. Ram Asrey, for whom my father also developed a great liking. As a student, he had led militant demonstrations and protests for freeing the INA prisoners and had suffered a severe lathi charge in one of them. He greatly admired my parents and spent time talking with them on a variety of issues.

Lakshmi grew to admire the sacrifices made by poor Party members who were workers in the mills, and her experience in the refugee camps in Bengal convinced her that the CPI(M) was very different from other political parties. Her homecoming was an amazing moment for me. From that time onwards, we were not just mother and daughter but comrades.

My mother joined the Party in a tumultuous time. Bangladesh had just emerged out of the decisive victory over Pakistan by the Indian army in the Western sector, while Indian army personnel fought alongside the freedom fighters against the Pakistani army that committed horrific atrocities there. This was Indira Gandhi’s moment of great glory, and unfortunately, it made her more authoritarian and determined to crush the Communists in West Bengal.

A general election was held in March 1971 and Indira Gandhi, flush with triumph, converted it into an Ashvamedh Yagna to gain control of the entire country. She did win a big majority, but the Congress horse was stopped by the CPI(M) and the people of West Bengal. The CPI(M) won 20 seats.

We had decided to contest the Kanpur Parliamentary seat to take forward our growing strength among the working class. Com. Ram Asrey would have been the natural candidate, but there were differences within the Party and Com. Shiv Verma—Bhagat Singh’s associate and the youngest prisoner in the Andaman Cellular Jail—was fielded as our candidate. Despite our disappointment, we campaigned tirelessly. By this time, I had the use of a small, old car which often had to be pushed to start. I used to drive it myself and had fitted it with a small loudspeaker for the campaign. One comrade would accompany me to make announcements. There was one who could also sing quite well and he made up a funny election song! I remember driving miles in that car and stopping at various street corners or in villages and addressing small meetings. We got 5,000 votes.

Immediately after the election, emboldened by the increasing authoritarianism of the Central Government, the management of factories where we had strong unions—JK Rayon and IEL (the fertilizer unit of ICI)—started cracking down. The Congress was in power in UP too. The workers in JK Rayon went on strike against victimisation and the management locked out the factory.

I saw at very close quarters what a strike meant for the workers. The meagre wages they earned meant they had no savings at all. Many were forced to take their children out of schools. I could see malnutrition and hunger entering homes that had earlier enjoyed good food. The women were haggard and harried. Those workers—many of them Dalits and some OBCs—who had some land in their villages, left Kanpur. But a large number stayed back. Despite all the hardships, the workers stayed united and determined. This was a very inspiring lesson for me.

The strike itself was such a lesson—the realities of class struggle and class solidarity were brought home like no book could have done. We went around labour colonies in the city collecting money, grain, vegetables, pulses, etc., for the strikers and, since this was something that we did several times in the next 2–3 years, we became familiar faces in working-class areas. I was amazed by the generosity of the poor. If they had little for their own families, they would give a few onions and potatoes. Workers from the Defence factories who were relatively better off would give two rupees or even five. If someone gave ten rupees, it felt like a fortune. We also went around the bazaars and here we would get abuse, criticism, and also some money.

The management of JK Rayon had decided not to communicate. This was a very difficult time. Finally, a manager from the JK Raymond factory in Thane, where there was a CITU union led by Com. Khobkar came to Kanpur. Com. Khobkar was very helpful in setting up talks with him. Com. Ram Asrey was an incredible negotiator. He was so persuasive, polite, humorous, and also talked about so many other things that he disarmed his listeners. It was a difficult negotiation. Finally, there was an agreement according to which some of the workers’ demands were met, but three of our leaders were not taken back to work. We had to agree to this, but we were able to appoint the UP CM, Kamlapati Tripathi, the arbitrator in this matter.

Tripathiji was a complex person. On the one hand, a very conservative Brahmin who expected people to touch his feet—but when I did not do this and, in fact, laughed a bit when the owner, Govindhari Singhania, placed his head on his feet—he turned to me with a smile and said, “Badi natkhat ladki hai!” (Very naughty girl!) He had been a freedom fighter and respected my parents a lot and that was helpful.

He was a difficult person to meet and making an appointment was almost impossible. At the time, a great friend of the family, Islam Ahmad, was UP IG Police (the highest rank at the time) and he was close to Tripathiji. He took me twice into Tripathiji’s house and told me to run inside to his pooja room where I was able to meet him. He told us that he could never support victimisation of even one worker but we would have to be patient. And he kept his word. All our leaders went back to the factory and there was much celebration.

Lakshmi had thrown herself into the struggle. Of course, she helped the workers’ families and treated them. She also started a weekly clinic in the area around the Rayon factory and kept it going for years.

0 comments