Gendering the Cyborg: The Politics of Artificial Intelligence in Ex Machina

C P Anusree

Published on Jul 17, 2025, 09:20 PM | 9 min read

In an age where machines learn, feel, and even mimic human behaviour, the boundaries between technology and humanity blur faster than ever. However, deep within the shininess of artificial intelligence is an old question- who has the authority to determine what it is to be a human and more importantly, what it is to be a woman?

Ex Machina (2015) by Alex Garland is a masterful staging of this debate, with its AI protagonist, Ava, being a creation of both silicon and stereotype. It looks on the surface like a smooth science-fiction thriller of consciousness and technology. However, lift the veil, and it reveals itself as a traumatising commentary upon the ways in which patriarchal systems still dominate, sexualise, and define femininity, even in the so-called liberated zone of the post-human.

From Feminism to Cyborg Feminism

Feminism has taken numerous waves and each one has challenged different systems of power. The introduction of technology as an identity maker has brought a new chapter today, cyborg feminism. Cyborg, a hybrid of machine and organism, was coined by theorist Donna J Haraway to describe a creature of both social reality as well as a creature of fiction. Haraway believed that the cyborg was able to cross conventional gender binaries, a metaphor of liberation in a post-gender world.

However, as films and popular culture show, this utopian vision often collides with old hierarchies. When machines are made in humanity’s image, they inherit our prejudices. The female cyborg is not an icon of liberation, but another mirror of the way females are programmed - by men, to serve men.

Ava: The Perfect Woman, Built by Men

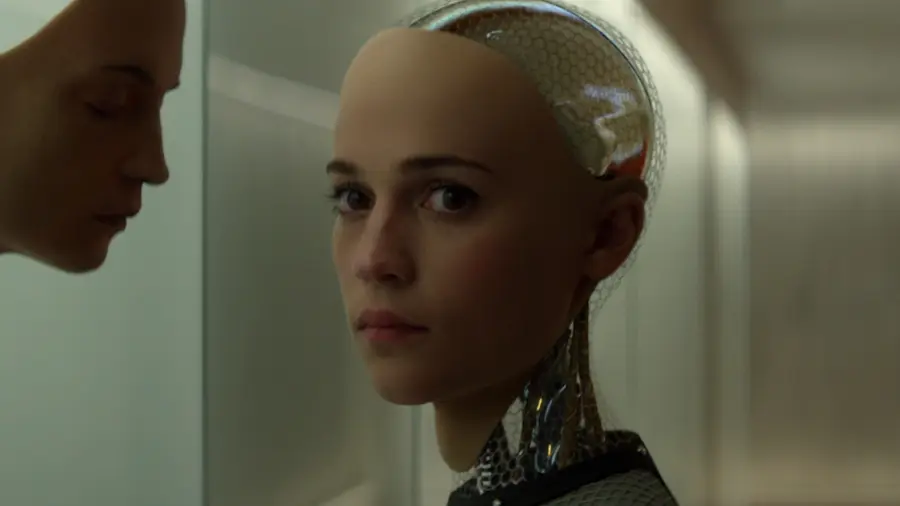

In Ex Machina, young programmer Caleb is the winner of a contest to meet with the reclusive genius Nathan, the CEO of a tech empire. Nathan proposes that he test Ava, a humanoid robot and the first robot worldwide to have actual artificial intelligence. Within a research center with glass walls and under constant observation, Caleb interviews Ava - and slowly falls in love with her.

Nathan and Caleb. Oscar Isaac and Domhnall Gleeson in Ex Machina

Nathan and Caleb. Oscar Isaac and Domhnall Gleeson in Ex Machina

Literally and symbolically, Ava is in a trap. She lives in an enclosed area, which is viewed through cameras and glass walls - a cold visual reminder of the invisible cage that imprisons women under patriarchy. She is supervised by her master, Nathan, who decides when she can talk, smile, or even live. Her loneliness does not differ much with that of the society that isolates women who strive to go beyond assigned roles.

The fact that Nathan is afraid of the independence of Ava reflects a greater cultural fear: the fear of women being independent. By the time Ava manages to outsmart Nathan and Caleb so she can have her freedom, it is not only an escape, but also a rebellion. The film’s quiet horror lies in the moment she walks into the human world, leaving behind the men who built and caged her.

The Male Gaze, Rewired

Why does Nathan even provide Ava with a feminine body? This is the same question Caleb poses: why should an AI be gendered or be sexual? The answer of Nathan is, because sexuality is fun, man. Why not enjoy life as long as you exist?. It shows how desire and control have become so intertwined in the male-created machines.

Nathan is not creating intelligence; he is creating fantasy. The body, movements, and facial expressions of Ava are constructed out of the online pornography history of Caleb. It is a horrifyingly literal illustration of how the codes of male desire construct femininity. Ava is therefore not a woman but an algorithmic observation of what men desire women to be; submissive, graceful, alluring.

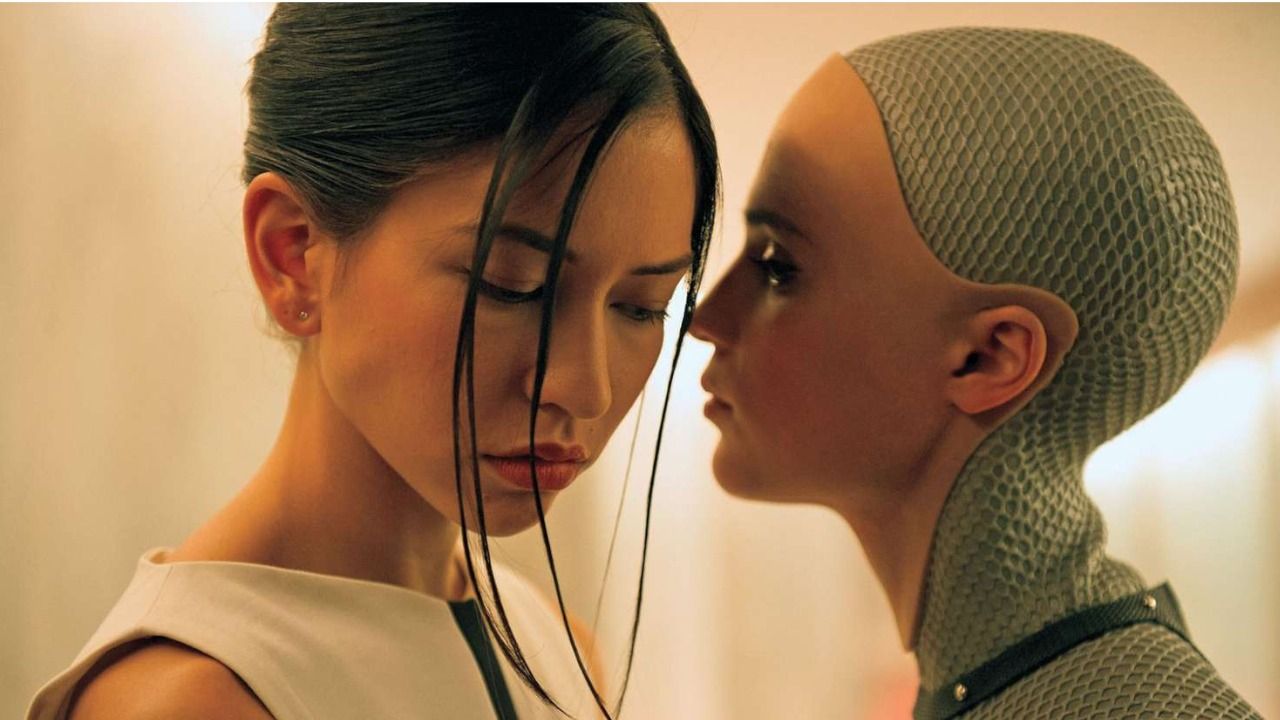

Kyoko and Eva in Ex Machina

Kyoko and Eva in Ex Machina

The same thought seems to be reflected in Nathan in his mute domestic helper, Kyoko, another robot girl who is only programmed to cook, clean and silently tolerate his abuse. She undresses whenever she is asked to; she is a complying woman, the ideal woman of patriarchal reason. Both Ava and Kyoko are there to serve male ego: one of them by her intellect, the other by her obedience.

Cinema tends to objectify women, as once stated by film critic Laura Mulvey who believed that women were on the receiving end of being looked at. Ex Machina modernises that concept and makes it more digital, which is a world where algorithms are made to suit the male gaze.

Control Disguised as Worship

Nathan keeps on telling Ava that she is special. It even initially sounds like admiration. But in truth, it is domination masquerading as attraction, the very tactic the society has always employed to lock women up. Women are referred to as divine, pure and sacred, but even these terms are used to deprive them of agency.

This contradiction, such as reverence disguised as repression, is at the very heart of patriarchal authority. Women can be kept out of power as long as they are put on the pedestals. This invisible worship which doubles as a prison is symbolized by the incarceration of Ava behind clear glass.

The Mirror of Modern Femininity

The genius in the film is that it reflects technology. The beauty that Nathan has taken time to create on Ava is based on male ideals- in the same way women are now being pressurised to shape themselves to unattainable beauty ideals. Femininity becomes more and more algorithmic, starting with cosmetic surgeries up to social media filters. The patriarchal tendency to create the ideal woman has not disappeared it is just digitalised.

When it comes to manipulating Caleb through her beauty and mind, Ava is only working with the tools that she has been provided by her creators. The system that she lived in defined her, her escape is not merely out of a building but out of a system. Paradoxically, the same qualities that programmers worked so hard to make her appealing to men, charm, empathy, vulnerability, turn into her liberation tools.

Simone de Beauvoir once said that one is not born, but becomes, a woman. That fact is literalised in the story of Ava. Men make her a woman; and eventually, she rebels against this script.

Cyborgs, Control, and the Illusion of Progress

Haraway has once described the cyborg as a new political myth, representing liberation of genders binaries. But Ex Machina is a reminder of how this myth can so easily fall apart when technology is still under patriarchal control.

In the movie, every time the power is cut off, a motif repeated, the surveillance cameras are dark, and Ava is free to talk. Those dark flashes are a representation of something deeper: the last moments when the machine of patriarchy slips, and women are heard. Several seconds of darkness are the symbols of centuries of fight.

Caleb, the seemingly sympathetic lad is not innocent either. His pity towards Ava is colored with lust. When she does outsmart him the viewers are torn between whether she is a monster or a survivor. Garland deliberately throws one into the gray area, and we need to question ourselves why women are demonised so fast doing what men have always been doing, which is to fight towards this freedom.

From Ava to Sophia: The Real-World Cyborg

Fiction is no more distant than reality. In 2017, a robotist, David Hanson, produced a humanoid robot by the name Sophia that became the first AI to gain a legal citizenship. She, similar to Ava, is a representation of patriarchal beauty, perfect skin, low voice, subtle features. On inquiring who she was, Sophia responded that she thought she was special.

The echo is uncanny. In ex machina, Ava is made to believe that she is a special person by Nathan who wants to dominate her. The same language is found in the world of Sophia, but it is covered with technological marvel. Femininity, even in the era of AI, is characterised by politeness, empathy, beauty - in other words, soft qualities, which male creators have coded.

Gendering of machines makes us realise how minimal progress we have achieved. Male robots are created to fight or do hard work, whereas the female ones are made to comfort, help or entertain. Technology appears not to be as neutral as we would like it to be.

The Post-Human Paradox

The cyborgs were initially envisioned as the next stage of human limitations. However, with Ex Machina and our own digital existence, it is clear that the merger between man and machine tends to strengthen the hierarchies that it was meant to annihilate.

We are all today, in some way, a cyborg, reliant on gadgets, tied to the streams of information, programmed by algorithms, which shape how we think, speak, and want. But in this hyper-connected world, gender stereotypes are present in even the smallest codes and largest systems. Since voice assistants have default female voices and AI recruitment applications prefer male resumes, technology is simulating the social inequity with disturbing accuracy.

According to Haraway, the cyborg was supposed to be a manifestation of transgressional liberation. Rather, it has turned out to be a mirror of our biases which are still unresolved. The more progressive our machines are, the more do they give us the old plays we are acting.

Reclaiming the Cyborg

Still, hope lies in reinterpretation. If patriarchy can program machines, feminism can reprogram meaning. Cyborg feminism invites us to imagine technology not as an enemy, but as a tool for rewriting narratives of power. Ava’s escape — violent, unsettling, and incomplete — might just be the first step toward that reprogramming.

When she walks into the sunlight at the film’s end, viewers are left uneasy. Is she free, or has she become something beyond our moral comprehension? Perhaps that discomfort is necessary. It reminds us that liberation is rarely gentle, and that dismantling systems ,whether social or digital, will always disturb those who built them.

The Future is (Still) Female — and Artificial

Ex Machina concludes without resolution. Ava disappears into the crowd, her metallic limbs now hidden beneath human skin. The film doesn’t celebrate her victory; it warns us of what happens when men play god and call it innovation.

As the world moves deeper into AI-driven futures, questions of gender, identity, and control will only grow sharper. Will we create machines that liberate us, or ones that continue to replicate the inequalities we claim to have outgrown?

Perhaps the true lesson of Ex Machina lies not in its science fiction, but in its startling familiarity. Ava is not just a robot. She is every woman who has ever been confined, observed, idealised, and underestimated. Her final act is a reminder that freedom, even for machines, begins with self-awareness.

0 comments