Economy

Britain’s Dark Shadow Over Indian Cooperatives

Anusha Paul

Published on Jul 26, 2025, 06:13 PM | 6 min read

The Union Government’s recently announced National Cooperative Policy is being projected as a visionary step toward rural empowerment and economic transformation. Aimed at tripling the cooperative sector’s contribution to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2034 and making it a pillar of the “Developed India by 2047” agenda, the policy outlines ambitious reforms—from upgrading primary cooperative societies into multi-service hubs to promoting organic farming and marketing local products under a unified “Bharat” brand.

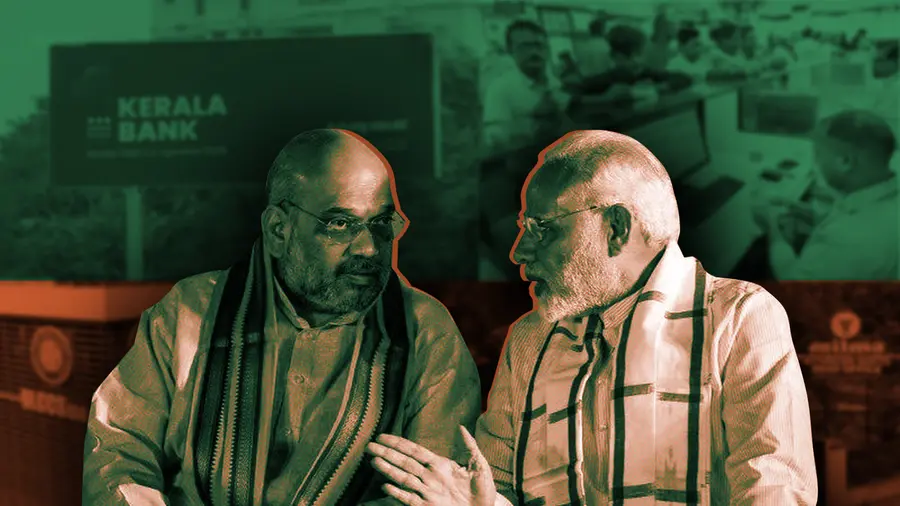

Beneath this developmental narrative lies a deeper, politically charged objective: a determined attempt by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)-led Union Government to bring India’s cooperative sector—long a symbol of community-led development and democratic decentralisation—under central control.

Kerala, where the cooperative movement is one of the most robust and community-rooted in the country. Kerala’s cooperatives are deeply integrated into the state’s social and economic fabric. They span rural credit, dairy production, housing, fisheries, and even health services—serving as engines of welfare. These institutions offer affordable credit to small farmers, sustain women’s self-help groups, and provide critical financial services where commercial banks often fall short. A striking example of this came during the 2018 floods, when cooperative banks provided immediate credit and relief, well before larger financial institutions responded.

Among the most successful of these initiatives is Milma (Kerala Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation), which operates through a three-tier system: village-level cooperatives, district unions, and a state-level federation. Thousands of small-scale dairy farmers—many of them women—contribute daily milk, which is then processed and sold under the Milma brand. What distinguishes Milma is its democratic structure: producers are not just suppliers but members with real decision-making power.

This participatory model helps bypass exploitative middlemen, ensures fair prices and timely payments, and provides support services like veterinary care and subsidised feed. In districts such as Malappuram, Palakkad, and Wayanad, Milma-linked cooperatives have allowed women to gain financial independence through home-based dairy units and self-help groups. Their income is regular, dignified, and community-controlled—a rare success in rural India.

Similarly, fishermen’s cooperatives along Kerala’s coastline—from Kollam to Kannur—help shield traditional fishing communities from market volatility. These cooperatives ensure fishers can negotiate better prices, access essential gear and supplies, and pool resources for fuel and maintenance. More than economic platforms, they serve as a buffer against corporate exploitation, offering social security, emergency credit, and a degree of collective resilience.

Under Entry 32, List II of the Indian Constitution, cooperatives are a State subject. The 97th Constitutional Amendment (2011) further reaffirmed that cooperative societies must be autonomous and democratically managed.

However, the new policy mandates that primary and district-level cooperatives affiliate with central apex bodies such as NAFED, IFFCO, and new entities like National Cooperative Organics. These bodies are not politically neutral. Their leadership often includes individuals aligned with the BJP-RSS network.

For instance, Jethabhai Ahir, appointed Chairman of NAFED in 2024, is a BJP MLA from Shehra, Gujrat. Influential political figures like Bhupendra Yadav, a former RSS pracharak and current Union Minister, play key roles in shaping cooperative policy, further centralising power and eroding local autonomy. The Ministry of Cooperation, set up in 2021 under Home Minister Amit Shah (himself an RSS leader), consolidated authority over cooperative societies previously managed by states, raising concerns about federal overreach and central control

Another layer of this centralisation effort is the push for uniform banking software across all cooperative banks. The Union Government justifies this as a step toward transparency and efficiency. But in Kerala, cooperative banks have adopted free and open-source software (FOSS) like “Sanghamitra,” developed locally with support from the Kerala State IT Mission. This system allows for technological sovereignty, data autonomy, and customisation based on local needs.

Replacing this with a centrally imposed, potentially proprietary system poses multiple risks. Sensitive financial data may be routed to central agencies and to the private companies, exposing cooperatives to top-down scrutiny and political interference. The flexibility and responsiveness that allow these banks to serve women-led enterprises, informal workers, and small farmers could be compromised by bureaucratic delays and rigid algorithms. Kerala’s use of FOSS reflects more than a technical choice—it’s a political and ethical stand against imperialist-capitalist surveillance and centralised control.

Kerala’s digital independence is part of its larger commitment to decentralised governance and people-centric development. The Union Government’s attempt to overwrite this with a homogenised, opaque system reveals an intent not to reform but to subordinate.

Compounding this, Kerala’s cooperatives have faced targeted action by central agencies. The Enforcement Directorate and Income Tax Department have launched multiple investigations, often based on politically curated vague allegations, despite the fact that financial irregularities exist in many BJP-ruled states without attracting similar scrutiny.

In Maharashtra, cooperative sugar mills and banks linked to BJP leaders have long faced irregularity allegations. In Gujarat, politically connected individuals have been implicated in manipulating credit societies. In Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, cooperative banks are often under-performing and poorly regulated. Yet, there has been no comparable ED crackdown or media outcry in these states.

Meanwhile, India’s recent Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the UK threatens to flood domestic markets with cheap agricultural and dairy imports. British dairy and agri-tech firms are expected to benefit, while Indian cooperatives—especially state brands like Milma—face the risk of being priced out. A centralised cooperative system aligned with national branding lacks the agility and local accountability to protect farmers and producers from such external shocks. The “Bharat” brand, if imposed, could override trusted state-specific identities like Milma, dismantling decades of community trust.

Great Britain’s return to India, cloaked not in imperial flags but in the polished suits of crony capitalists and neo-fascistic regime, signals a dark resurgence of economic plunder under the guise of free trade and cooperation. This alliance—between British agri-capitalists and India’s political elite—threatens to deepen the exploitation of India’s farmers, fishermen, and cooperative workers, pushing them into the shadows of corporate monopolies and centralised authoritarian control.

The promises of growth mask a ruthless agenda of resource extraction and cultural erasure, where local identities and hard-won democratic spaces are bulldozed for profit. It is a clarion call to resist this neo-colonial onslaught—not with silence or compliance, but through unified grassroots defiance, reclaiming our cooperatives, our data, and our democratic rights from the clutches of this crony capitalist nexus. The fight for India’s soul is now more urgent than ever.

0 comments